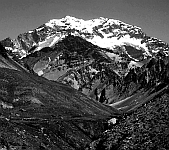

The wind hadn’t calmed by morning, so I just lay there until the sun had warmed the tent a little, before opening the door to peer at the weather. The wind was considerably less than in the night, but it was clear that some sort of weather system had arrived. The summit was shrouded in mist. Although there was nothing like the spectacular display we had witnessed from Plaza de Mulas, I could see that the wind higher up was far too strong for the day to have been a summit day. I had a leisurely breakfast, and eventually got up to find out who was doing what. Not surprisingly, Tim was still there. Jim and Dan were starting to pack up, ready to move everything up to Berlin Camp as planned. The Canadians were doing likewise. Tork was looking rather miserable – the wind had deprived him of most of another night’s sleep.

I had a brief word with two young Americans who had made it to the top the previous day. They said there was hardly any wind at all on the top when they were up there. Clearly I had arrived at Nidos twenty four hours too late. Even if I had known early on Saturday morning that Saturday was going to be the perfect summit day, and that the weather was subsequently going to turn bad, there was still no way I could physically have gone up that day : acclimatisation held sway over the itinerary at this altitude.

I went and stayed in my tent for several hours, to get out of the wind. I had lunch, and then tried to melt some more snow. It was very frustrating, as with the increased wind it was barely possible to set the stove so that it wouldn’t blow itself out. The problem was compounded by the fact that the candle wouldn’t stay alight either. I attempted to block the gaps under the flysheet through which the wind was coming, but even so the stove would only last a few minutes before going out. Nevertheless I persisted, and after a couple of hours of hard labour I again had all water containers full.

I had no inclination whatsoever to move up to Berlin camp. I felt, however, that my acclimatisation had got to the point where it would be useful to climb up there anyway for the exercise, and maintain red blood cell production. I didn’t take anything with me – the Canadians had said it had taken them between one and two hours to get to Berlin carrying loads, so I didn’t expect to be gone for long. The climb was steep, ascending a series of zigzags on the north side of the ridge. I checked my ascent rate with the altimeter on my watch, to compare it with the rate that I had managed on the first carry to Canada Camp. I was managing five metres per minute, which was very respectable at an altitude of nearly 6000m, even though I wasn’t carrying anything. I couldn’t help calculating that at this rate I could be at the summit in only four hours…

After forty five minutes climbing the zigzags I noticed some debris of a structure of some sort, a little way above. I knew there was a ruined refugio at Berlin Camp but I couldn’t believe that I had already arrived. As it turned out what I could see was indeed Berlin Camp, but “a little way above” at sea level is not the same as “a little way above” at 6000m. It was fifteen minutes before I had got level with the structure, which indeed turned out to be the remains of a hut. The hut appeared to have been blown off the ledge it had been built on; the remnants lay strewn all over the boulder slopes just below. I arrived on the ledge to find there were two more little huts still intact : simple A-frame structures that looked big enough for perhaps three people each. Around them were a few tents, including Jim and Dan’s yellow North Face dome tent.

There seemed to be a social gathering going on round on the west side of one of the huts. Half a dozen people were leaning on the sloping structure, soaking up the suns’ rays, and sheltering from the wind. Dave “Smiler” Cuthbertson was there, looking rather left out, and as a result not living up to his nickname. His American-Argentine buddy was there but was speaking Spanish with the others, who all sounded Argentine. I said a few words to Dave, and couldn’t understand why he looked at me with a rather blank expression. Eventually I realised it was because I had spoken in Spanish – it must have been the effect on my brain of my having just arrived at 6000m.

I chatted to Dave for over an hour : it was quite pleasant there, as a rocky outcrop was blocking the wind, and the west side of the hut was something of a sun trap. Dave said he and his client would be heading for the summit the next day, all being well. He was a lot more sociable than he had seemed a few days previously, and was keen to know a bit about what I’d seen in the Andes. He knew very little about the range. His backyard was the Himalayas – he said that there was no shortage of work for him as a guide, during the Himalayan climbing season. I asked him about the state of British mountaineering generally – who were the up and coming stars. He bemoaned that so many of the best known British climbers of his generation had been killed – he said he’d known many of them.

One amusing observation that Dave made was that it was obvious that I didn’t go in for buying the latest gear just for the hell of it. My rucksack, a Karrimor Jaguar 4, was bought in 1980 with a lifetime warranty, at a time when internal frame rucksacks were still relatively innovative. Even after the rough treatment it was receiving on Aconcagua, it showed no signs whatsoever of wearing out – remaining just as comfortable and practical as it had been eighteen years before. Dave was the only person who recognised my Phoenix Phantom – the tent had been the state of the art in lightweight one/two-man mountain tents when I bought it in 1980. Everyone else on Aconcagua looked at it rather curiously – it seemed to be the only lightweight tent on the entire mountain that wasn’t a dome tent. No doubt some people were sufficiently young to have never used, nor possibly even seen, any type of lightweight mountain tent other than a dome. It is true that dome tents are less cramped for a given weight; however, in terms of brute strength, the streamlined “external A-pole” design still seems to be inherently superior.

In the end the sun started to weaken, the wind started to increase, and it was time to head down. A mere fifteen minutes later I was back at Nidos, and went to tell Tork how I had got on. He was still trying to catch up on sleep, and seemed no happier than he had been earlier. I wandered back to my tent to warm up, and have some food.

The wind was still increasing, and I went out just as the sun was going down, to check that everything was still secure. There was a lot more cloud around in the western sky than I’d seen up until then. Most of it was below the level of Nidos, but there was one broken layer above. The scene became spectacular as the setting sun shone red between the two layers. It was very difficult to take a photo because the vicious gusts of icy wind made it almost impossible to keep the camera still.

The chill factor was probably already fifteen degrees below zero, and increasing, so I didn’t hang around long before diving back into my tent. I could have stayed outside if I had got out my down jacket, but I had so far managed without it. It was rolled up to try to keep its volume down, and would require a lot of effort to roll it up again.

I kept both draw cords on the sleeping bag as tight as they would go. This successfully kept the cold out, but unfortunately nothing could keep the sound waves out – it was a very noisy night.

Your Jaguar 4 rucksack brings back memories . . . I had one of those too. Coincidentally I also had a Karrimor Good Earth rucksack like the one that you took on your round the world trip. I guess it must just have been that at that time those sacks were so obviously ahead of the competition and not outlandishly priced. I don’t know what your experience was, but mine was that they were pretty much completely waterproof. No rain covers then. And I don’t recall ever having to put everything in plastic bags inside them. Some things haven’t improved!