I slept badly on the night of 18th January. Again the wind was howling in an infuriatingly sporadic manner. Sometimes it would calm down and I would drift off, then I’d wake up suddenly as a gust rattled the tent and I’d listen out for any signs that the flysheet was coming adrift. A few times I opened the inner tent to make sure the gear left out in the “porch area” was still there, and the flysheet still intact.

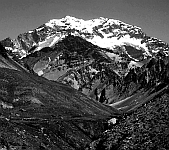

At daybreak the icy wind was still buffeting the tent most enthusiastically, so I stayed in my sleeping bag for as long as reasonable. Eventually I ventured outside. It was a cloudy day, and looking up I could see the mist still shifting somewhat briskly over the summit. It felt a lot colder without the sun shining. I found that there was a lot more ice in my water bag than previous mornings, even though it had been right next to my sleeping bag. I fetched some more snow after breakfast, and heated up some water to melt the contents of the water bag, as without the sun I doubted if it would otherwise melt. In fact, as my cooking pot was not big enough to hold meaningful amounts of snow, my technique for producing water had been to stuff snow into my water bag (an MSR Dromedary type with a wide cap) and then pour in hot water from the cooking pot. A couple of large mugfuls of hot water were generally enough to melt the two litres of snow in the bag, and produce water tepid enough to melt further snow that was shoved in.

One trick I soon learnt in relation to this was never to use up all my liquid water. I found it was remarkably difficult to melt dry snow in my cooking pot unless there was already some water in there. Without water to “prime” the process, the snow would just sizzle in the hot pan and evaporate. This sublimation straight from ice to water vapour seemed to be a phenomenon of high altitude. One of the Canadians had said that she thought that sublimation was part the reason for the formation of the penitentes. The combination of low pressure, low temperature, high wind, and very dry air would to make the formation of significant amounts of liquid water very difficult. Once the sun manages to melt the surface of the snow, the dry wind immediately evaporates the water, cooling down the surface and turning any remaining water back to ice.

The day wore on, and the wind persisted. I was reluctant to get out of my tent, and still more reluctant to think about moving it anywhere else. However, I was getting seriously fed up with this spot, and being constantly buffeted by the turbulence coming over the little protecting ridge. I tried to decide what to do. Tim would probably stick around in Nidos but Tork might well be about to move up to Berlin with everyone else. The original plan with Tim and Tork had been that after resting at Nidos on the Saturday, that we would then spend Sunday moving up to Berlin, with Monday and Tuesday as possible summit days. It was now Monday afternoon, so time was running out for Tim and Tork. In fact this was already Tim’s second “lost” summit day, as he seemed to have decided to do the summit from Nidos, and had been all set to go up the previous morning. However, Tim had said that although his plan was to head down on Wednesday, he could if necessary spin out his food supplies. He didn’t have such a tight time constraint with respect to his flight as Tork did.

My speculations about what the others might be thinking of doing was brought to a sudden end soon after midday by a shout from outside the tent. It was Tork. He announced he’d had enough and was heading back down to base camp. He’d hardly slept at all with the incessant wind, and needed to get down to recover. He said it was possible that after a day’s rest at lower altitude he’d restock, and have one last attempt if the weather improved. He said that there was a forecast predicting three days of high winds, and that all eleven remaining Canadians had given up and were on their way back to base camp. Dave Cuthbertson and his client had also thrown in the sponge as they couldn’t afford to wait three days – they had their flights to think about. Smiler’s American-Argentine friend was also heading down along were several other people who had been at Berlin with him – it was presumably he who had received the duff forecast over his handheld radio. It was easy to believe his forecast this time : Tork said that several dome tents in the main part of Nidos had blown down overnight.

Tork said that Tim had refused to go with the flow, and had gone up with his tent to Berlin Camp. There was no sign of Jim and Dan, so it was presumed that they were holding fast at Berlin. Having made the decision to quit, Tork was keen to be off, and we said our goodbyes.

I had lunch and mulled over what to do. Before Tork had come by, I had been torn between the appalling effort of moving elsewhere and the insufferable prospect of staying put. The fact that all the people who I knew had now left Nidos and were either up at Berlin Camp, or on their way down to Plaza de Mulas, made remaining at Nidos even less attractive. Thus the balance was firmly tipped in favour of getting the hell out of Nidos. That just left the question of whether to go upwards or downwards.

It really was most off-putting that so many people were giving up and going home. I could almost claim it was a little inconsiderate of them all, as they made anyone who didn’t go down look rather reckless. I had no desire to be classed in the same league as an “upwards ever upwards” Japanese. However, I could find little reason myself for going down : I felt adequately fit and strong, and from what I could tell appeared to be well acclimatised. Furthermore, all my equipment (with the possible exception of my stove) seemed to be bearing up admirably. I hadn’t even had to use my warmest clothing yet, and I still had six days’ worth of food with me. Furthermore, I knew that if conditions started getting seriously bad, I could get down to base camp in a little over an hour, even from 6000m. If I had known that there was nobody at all in Berlin Camp then it would have been a tough decision whether to go up or not. However, that Jim, Dan, and Tim were there made it very easy to decide to strike camp and move up to 6000m.

I decided to leave my ice axe and crampons at Nidos, as everyone said that there was no point whatsoever in taking them up : the north-west ridge was completely clear of snow. I also left a day’s worth of food in my little day sack. I put everything that I was leaving inside a dustbin liner. I then sealed it with tape and left it with some rocks on top of it against the little wall that had protected my tent for three days. Getting the tent down was an effort in the strong wind, but by mid afternoon I was ready to say goodbye and good riddance to Nidos. I was vaguely aware that however gusty, cold, and unpleasant it had been here, it was bound to be gustier, colder, and more unpleasant higher up. However, I felt sure that moving higher up the mountain would give me a temporary psychological boost that was worth several degrees centigrade of coldness, and several decibels worth of flapping tent.

My only nagging practical concern was that my fitness would seriously deteriorate if I spent too long at Berlin Camp : at an altitude of 6000m it was just inside the death zone.

I’m curious . . . what’s the source of the video clips? I assume they are authentic and not reconstructed. So whose was the video camera and what technology was it using?

David, I’ll reveal all once I get to a lower altitude and can talk (I’m currently taking 10 breaths for every step, up near the top of the Canaleta…. 😉 )