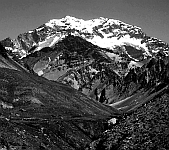

As I headed over to the north side of the ridge and began the ascent of the zigzags, I noticed how many tents had disappeared from Nidos. The empty spaces everywhere suddenly brought it home to me that by not having given up yet, I now belonged to a small minority. Although an overabundance of people can often spoil an experience in the mountains, up until that point the ascent had been socially very enjoyable. It was good fun to see the same familiar faces at successive camp sites, swap stories and give mutual encouragement. Now it felt as though the centre of activity had moved elsewhere leaving a few of us stragglers behind. It was like a New Years eve party which goes well until 11:30pm, at which point, for no apparent reason, most of the people suddenly say they’re going home. The suspicion is that they’re really all off to bring in the New Year at some other party, and the few who are left feel miserable that they’re no longer where the main action is. The mystery in this case, however, was that the people who had left early really were going home. There is only one summit on Aconcagua, and the responsibility for reaching it now rested with a few of us stragglers who, for better or worse, had been left behind.

As I plodded up the zigzags, I kept pondering over the question of why so many people had given up completely, just because of the probability of three non-summit days. Considering the positive mood that everyone seemed to have had just two days previously, it was very hard to fathom.

Everyone had invested so much time, effort, and money in reaching Nidos. Surely the prospect of sitting patiently in a tent for three more days wasn’t such a huge sacrifice to make, if the alternative was to return home in defeat? People had said they were fearful of missing their flights home – but the penalty charged by an airline for changing the date of the return leg of a ticket is microscopic compared with the total cost of a trip from Europe or North America to climb Aconcagua. Perhaps some people were scared to be late back for work – yet what sort of employer could fail to be forgiving when offered the excuse that the three days of extra absence were due to being stranded by two hundred kilometre per hour winds at 6000m in the Andes?

It was also difficult to believe that people could have brought so little food with them that they couldn’t afford to wait a few more days : everyone apart from me had used mules to bring in their supplies. I had brought everything myself, yet I easily had enough to now spend five days at Berlin Camp. Shortage of food couldn’t be the problem. But there was clearly something which had persuaded people, the same people who had so recently been keen to reach the summit, to suddenly change their minds and head home in their droves. The cold perhaps? But from what I could see, everyone had top quality gear, down jackets, plastic boots, five season sleeping bags and so on. People were prepared for the cold, at least physically.

Suddenly it dawned on me what had almost certainly been the greatest factor in persuading so many people to throw in the sponge. It was something that everyone had been somewhat prepared for physically, but which nobody had been prepared for psychologically. It was something invisible, inescapable, incessant, and infuriating; something that can drive people insane. It was something that I had gradually become used to over five summers working in southern Patagonia, but which had still got on my nerves at Nidos more than anything else. A forecast for three days more of it had been too much for most people.

It was the wind.

I hauled myself very slowly and wearily up the last few metres to Berlin camp. It looked very different from the previous day. Gone were the tents, gone was the little social gathering in the sun by the side of the refugio. Berlin Camp was cold, cloudy, windy, and looked almost deserted. There was just one inhabited tent, which contained a rather forlorn looking Tim. He seemed pleased to see me. I asked him where Jim and Dan were – it looked as though Tim was the only resident at Berlin Camp. Tim pointed at one of the little refugios, explaining that Smiler’s buddies had been staying in it, and when they cleared out in the morning Jim and Dan had pounced on it. Tim said there was probably room for me in there, if I didn’t fancy putting up my tent. He told me that in the other refugio there were a couple of Spaniards who were unlikely to stay long. And Smiler? And his client who had paid so much to be brought from the UK to conquer Aconcagua? They had given up and gone down…

The more I thought about the fact that an experienced and well-known Himalayan mountain guide had decided (and persuaded his high-paying client) that Berlin Camp was not a good place to be, and that their summit attempt on Aconcagua should be abandoned, the more uncomfortable I felt… Tim, too, seemed to be resigned to the fact that he wouldn’t be making it to the summit. He clearly believed the weather forecast, and seemed to have come up to Berlin Camp merely for the hell of it, and push the frontiers a little further.

I suddenly had scary visions of me being the sole occupant of Berlin Camp within a matter of hours! I went to see what Jim and Dan’s plans were…

I stuck my head in the door of the refugio and said hello. Jim and Dan said there was room for three in the refugio, so I was welcome to join them. As I crawled inside, and propped the door back up to try to close the gap, there was a wonderful silence. All of a sudden the roar of the wind and the noise of Tim’s tent flapping seemed to disappear almost completely – it was ecstasy. I asked Jim and Dan what their plans were. It was quite a relief when they said that they had every intention of getting to the summit, and would wait at Berlin Camp for up to a week if necessary. This sounded more like it, though it was probably far easier for them to say this having installed themselves in the magnificent serenity of the refugio than it would have been if they had been sitting in a flapping tent outside.

Jim and Dan were cooking up some food that the previous occupants had left – it smelled rather good, and there was lots of it. Thankfully, a third of it was soon lobbed into my mug, and I felt much restored. Suddenly this was all very civilised.

The refugio was effectively a wooden three-man ridge tent. It wasn’t exactly warm – we all agreed that a tent would be warmer. It was very dingy as there was only one tiny and rather opaque window at one end. It was a little draughty because there was only half a door, and we had to prop up a sheet of plywood from the ruined hut to try to block the entrance. The doorway itself was only eighty centimetres high, so getting in and out was a question of crawling. Nor was it possible to stand up straight once inside – the roof was too low. However, it was very easy to forgive all these failings, simply because the hut was so marvellously, miraculously, quiet.

I noticed the difference in altitude, especially at first. Any movement of a major muscle required an extra few puffs from my lungs to replace the oxygen used. The effort of going outside to fetch something from my rucksack would leave me panting and with a pounding heart. The temperature was several degrees lower than at Nidos, and before long I got out my down jacket. The effect of putting it on was immediate – instantly I felt warm and snug. It was like wearing a sleeping bag. My expedition-weight thermal long johns made their first appearance and were hurriedly put on under my fleece-lined trousers. This made a difference, but it was clear that the default position during the day was to be inside one’s sleeping bag.

In the end, I never found out if my stove would have coped with operation at 6000m. Jim and Dan’s MSR stove was permanently set up in the corner of the hut, and it was pointless to get mine out. I was only three hundred metres higher than at Nidos, so I suspected that mine would just about have still worked, but melting snow would have been even more time consuming than before.

The wind increased as the daylight faded. There was an empty dome tent close to the hut, and we noticed that it was beginning to break free of its moorings. An empty tent was a worrying thing to see at the highest camp on Aconcagua. Empty tents on mountains can look so innocent and inconsequential to the uninitiated. Yet : how many times has an empty tent in some lofty or remote spot been the only material evidence that is ever found of the untimely demise of its owner? Jim and Dan couldn’t remember if there had been anyone in it the previous night, nor could the two Spaniards in the other hut. Clearly there was no point in leaving the tent to be ripped to shreds, so we slipped the poles out of their pockets, laid the tent flat, and put a few rocks on top. As we did this I noticed a head torch inside – this seemed to indicate that its owner had only expected to be away for the day. Clearly if the tent was still empty the following morning we would have to find a way to report it to the guardaparques.

The temperature kept dropping as night fell. It turned out that the meal that Jim had been preparing at 5pm when I arrived had been lunch, not dinner, and at about 9pm some more grub was dished up, this time by Dan. There seemed to be no shortage of food – the other two had brought enough food for nearly a week, so what with the extra that had been left we could afford to eat rather well. Once the stove was off the temperature in the hut plummeted – I decided to put my 1.5 litre plastic bottle inside my sleeping bag that night to stop it freezing. This I did with some trepidation : had the bottle split it would have caused serious quantities of discomfort…

I slept in the middle, with my feet by the door. I kept all my clothes on apart from my boots and down jacket. Even so, I was cold in the night – the temperature was probably around minus fifteen C in the hut. I had to drape my down jacket over myself, depriving myself of my pillow. I decided that on subsequent nights I would have to keep my jacket on inside the sleeping bag. My Therm-a-Rest mattress performed well – I was never aware of losing heat downwards. I slept on and off, and was aware of the suffocating feeling of high altitude every time I awoke.

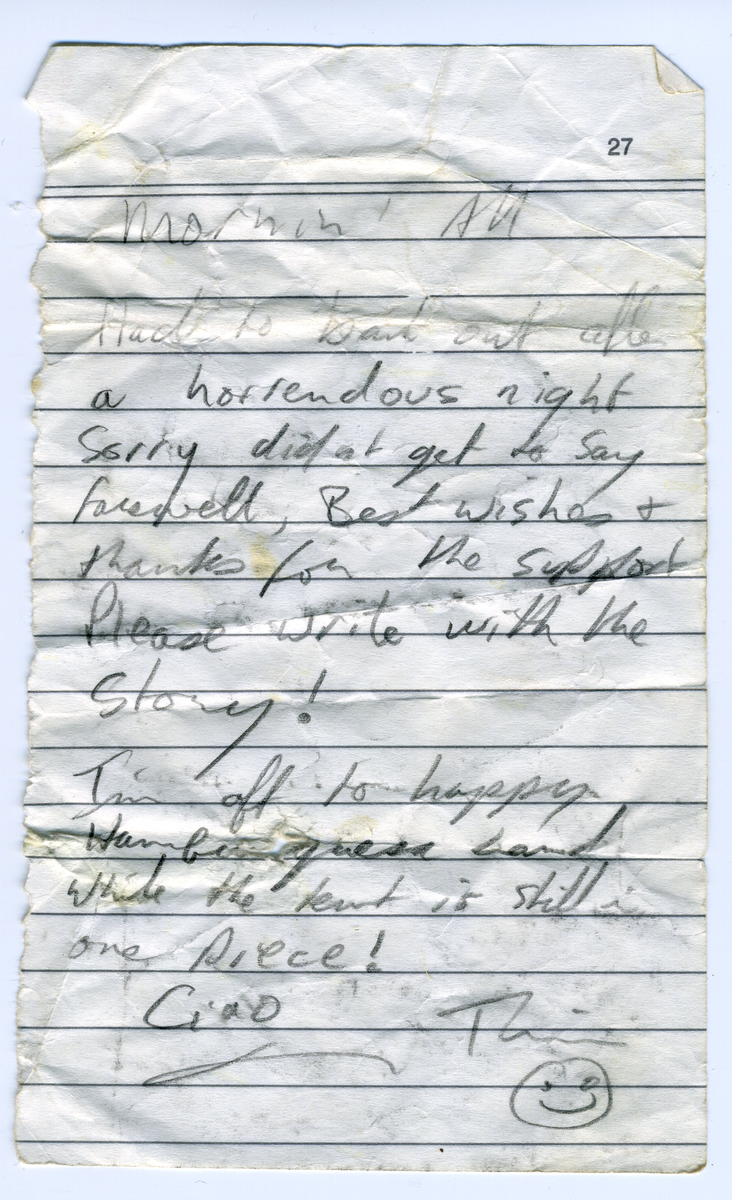

At first light it was clear that there was no chance of this being a summit day – the wind was still as persistent as ever. It was also desperately cold. An hour or two later I woke up again to hear Jim announce that he had found a written message from Tim inside the door of the refugio. In the note Tim said he had had a miserable night and was heading down to base camp. He wished the three of us who remained the best of luck.

“Morning All, Had to bail out after a horrendous night. Sorry didn’t get to say farewell. Best wishes and thanks for the support. Please write with the story! I’m off to happy Hamburguesa Land, while the tent is still in one piece! Ciao. Tim”