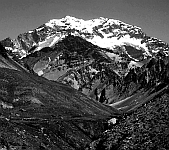

My toes felt somewhat numb as I started up the first steep section towards Piedras Blancas. I knew that the rule was that if after an hour one’s toes are still uncomfortably cold, then give up and go straight down. If the first hour’s walking doesn’t warm them up, then they’re not going to warm up, and there’s a good chance that they’ll end up getting frost-bitten. Not only is it colder higher, but it’s not possible to move so fast in the thinner air, and thus the body generates progressively less heat as the day goes on. I started wiggling my toes like mad to try to warm them up. My rapid toe-wiggling was in marked contrast to the rest of my movements, which were all in exaggerated slow motion – rather like a swan swimming sedately along the surface while its unseen legs waggle furiously.

As I emerged on the more exposed shoulder above Berlin Camp, I realised that there was still an appreciable amount of wind : the chill factor was wicked. Luckily the wind was from behind, so I didn’t feel the wind on any exposed part of me.

Despite the wind, within twenty minutes I was feeling comfortably warm, apart from my thumbs and my toes. My thumbs were clamped round the handles of my ski sticks, and even though I had heavy Thinsulate-lined gloves with down-filled overmitts my thumbs were soon hurting with the cold. I tried to bring my thumbs into the main part of the mitt, and curl my hand over the top of the stick to hold it, but this wasn’t very easy. In the end I got my spare mitts out – my good old Helly Hansen Polar Mitts – and put them on under the down mitts instead of the Thinsulate gloves. There was an immediate improvement.

The Brazilians had left just before me, and I was slowly following them up the zigzags. Their pace was extremely slow, but then it has to be at that altitude. Then I decided that it didn’t have to be quite that slow, and I found a short cut to sneak past them. There were about a dozen more people spread out in front – mostly in small groups, with one or two individuals. There was nobody who I knew. It seemed rather ridiculous to be surrounded by total strangers at this stage, having made so many acquaintances over the previous two weeks.

I continued to feel warm – almost too warm – but my right big toe still felt very strange, almost as though there was something wedged between the two largest toes. I knew there wasn’t, and I kept wiggling my toes furiously to try to warm them up. I had felt the same thing on the left foot at first, but the sensation had gradually disappeared. However, the right toe was obstinately remaining half frozen, and would need some attention sooner rather than later. I had been going for over an hour when I saw that up ahead I was about to get to the top of a rise and emerge in the sunshine for the first time. I decided that I would stop there, and only go on if I could unfreeze my toe.

Coming out into the sunshine was wonderful – the perceived temperature suddenly leapt by twenty degrees Celsius, and the whole mountain seemed to get less hostile. I found a place to sit out of the wind, and took my boot off. I briefly inspected the toe – it looked a little white on the inside where it felt numb, and was cold to the touch. I put an already warm Helly Hansen Polar Mitt on the end of my foot, and sandwiched the toe between my gloved hands. The rest of the foot was fine – it was just this one bit of my toe that seemed half frozen.

To my left I saw a couple with whom I had earlier exchanged a few words at Berlin Camp – the girl had similar problems with her hands, but rather worse. She was failing to suppress her tears as her companion tried his best to warm up her hands for her. He probably didn’t succeed : I didn’t see the two of them again. Apparently ridiculous numbers of people lose fingers and toes on Aconcagua every year as a result of frostbite. The danger is that frostbite is so insidious – initially the finger or toe hurts with the cold, and then the pain fades as numbness sets in. In the heat of the moment the absence of pain can be mistaken for an indication that all is now well, and is ignored. The digit can then proceed to freeze solid at its leisure, after which there is often no option other than to have it chopped off at some later date.

A few of the people I met lower down had been talking with an old Aconcagua veteran at Puente del Inca, who had been issuing advice about the importance of good boots to avoid frost-bitten toes. He added that of course this wasn’t a problem for him. Someone had then asked if this was because he had excellent circulation in his feet. “No”, he had replied, “it’s because I lost all my toes on Aconcagua years ago.”

That only half my toe was numb was a good sign, and after about fifteen minutes sensation slowly returned to the whole toe. I spent ten more minutes at that spot, trying to force myself to eat chocolate and peanuts. I seemed to have lost my appetite completely. There was no sign of Jim or Dan. I left just as the Brazilians showed up, looking half dead.

I was gradually dropping into a rhythm; however it wasn’t a pacing rhythm but a breathing rhythm. The atmospheric pressure showing on my watch was now only 450 millibars – less than half the pressure at sea level. Under these conditions there was so much time between one step and the next that rhythmic pacing was impossible. Instead, the rhythmic signal that I would normally be sending approximately once per second to my legs, to tell them to take another step, was redirected to my lungs. I counted these signals, and once every three or four “steps” I took an actual step. I made my brain believe that it was the effort of my lung muscles that was physically pushing me upwards, and that the leg movements I made every so often were purely incidental. This psychology worked well, and I seemed to be going faster than most people.

The temperature seemed to be rising slowly, and the wind, if anything, was dropping even though I was gaining height. It appeared that all I had to do was to hope I could keep up this steady progress until I reached 6960 metres. Unfortunately the notorious Canaleta was something of an unknown quantity, and still some way above me.

Three quarters of an hour later I was nearing the top of a series of steep zigzags when I decided to stop for another breather, and to drink some water. Breathing so much dry air was drying me out rather fast. Luckily most of the water in my water bottle was still liquid, but ice was starting to form. Looking back, there was still no sign of Jim and Dan. There were many people dressed in red jackets – one was about to pass where I was sitting – but Jim and Dan would be identifiable because they were two people, both in red, one of them tall and of medium build, and the other fairly short and thin. There was no way of identifying people other than by their height and their clothing, because the only visible facial feature was the end of their nose. This was brought home to me a couple of seconds later, when the person in red who was about to pass me said “hello” in a voice that sounded very similar to Dan’s : it was, in fact, Dan.

He had started off with Jim, but Jim was going very slowly and had suggested that Dan go on ahead and catch up with me. Dan wasn’t carrying a rucksack : nor, as it later turned out, was Jim. Dan was curious that I had brought mine with me. I wasn’t carrying a great deal in it, but at least I had water, food, a bivouac bag, my head torch, spare gloves, waterproof trousers and cagoule. Dan appeared to have his camera in one pocket, a small water bottle in the other, and that was about it.

We carried on up the zigzags, and in half an hour arrived suddenly at a small flat area, with a seriously damaged A-frame shelter. This was Refugio Independencia – at 6500 metres ostensibly the worlds highest permanent structure. Whether this was true or not, it deserved a photo, and I was relieved to find that my camera seemed to have warmed up – it no longer gave the low battery warning light.

It was good to have an altitude check – the altimeter on my watch was no longer working. In theory it worked only up to 6000m, but I had earlier duped it by telling it at Berlin Camp that it was only at 5000m – by putting in a 1000m offset. This succeeded in fooling it up to about where I stopped to thaw out my toe. After that it apparently decided that enough was enough and subsequently refused to register either altitude or atmospheric pressure until the descent.

There were a dozen people sitting around near the refugio, and we stopped for another rest to give Jim a chance to catch up. Half the people sitting around seemed to be part of a guided group, led by a quiet-spoken girl with a Chilean accent and unassuming appearance. I wondered whether this was the group from the Santiago based company Azimuth, with whom I probably would have come if I hadn’t decided I could come independently. This Chilean guide, for all her modest manner and lack of stature, simply radiated confidence, and was the only person I had seen since leaving Plaza de Mulas who looked as though she felt totally at home where she was.

Peering downhill there was still no sign of Jim. We headed uphill once more. Up ahead the north-west ridge was becoming steeper and better defined – more steep zigzags appeared to lead to a narrow crest. Half an hour later we emerged on this crest, and realised that this was where the Normal Route left the north-west ridge and began to cross the upper part of the Gran Acarreo into the bottom of the Canaleta. The wind had dropped almost completely, and this was an excellent vantage point. Dan decided that he would wait here a full thirty minutes for Jim, and after that simply head for the summit – it was pointless to wait around indefinitely. Jim might have given up and gone back down – he wouldn’t exactly be the first to do so. Also Jim would know that his inexperienced but very fit buddy would probably catch me up, and be OK once he was with me.

I carried on slowly across the top of the Gran Acarreo. I could now see up into the first part of the Canaleta. There were not as many people in front of me as I had expected – the people who left Berlin Camp just ahead of me must have been the first batch. Even so, I estimated that there were at least forty behind me. What with the dozen or so I could see in front, there must have been over fifty who had set off for the summit that morning from Berlin Camp and Nidos combined. It was going to be crowded on the summit, I thought to myself.

A little further on I saw a group of three people coming very slowly down towards me. As they got close it was clear that the first person was being helped by the second one : this second one called out to me to please let them past. The first person had his arms stuck straight out in front of him as though he couldn’t move them. We were later told that the reason he couldn’t move them was that his forearms were literally frozen solid. We were told he was Belgian : he and his Brazilian companion had been forced to bivouac near the summit the previous night, on the way up from the Polish Glacier on the other side. He had suffered severe frost-bite, and it was reckoned that he would soon be having to get used to life without any arms. His Brazilian companion had frozen to death.