Lying on our backs remained the only acceptable activity for quite some time. Eventually I sat up and drank the rest of the liquid water in my bottle – about a quarter of the bottle was now ice. I also tried to force down a square or two of chocolate. There was no hurry to go anywhere – I estimated it would take two and a half hours to get down to Berlin Camp. The conditions on the summit remained almost flat calm and I didn’t feel that I was going to cool down too much by sitting and relaxing for an hour.

It wasn’t like the normal situation when reaching a summit. Normally one arrives hot, due to the heat energy generated by the ascent. When the energetic activity suddenly stops, the body rapidly cools down, limiting the amount of time that can be spent on the top. On Aconcagua, however, the rate of energy output on the ascent was minimal – 90% of the time I was just standing still. Thus going from being stationary 90% of the time on the ascent, to being stationary 100% of the time on the summit, wasn’t a major transition. This serves to highlight an important point about high altitude : if one gets cold, the only way to warm up is by putting on more clothes. It’s never possible to warm up by moving, because the rarefied air doesn’t contain enough oxygen to enable the body to generate any extra heat. It only contains enough to keep the lung muscles pumping away, and, with luck, to take the occasional step forwards. I had been warm on the ascent only because I was well insulated and because the conditions were favourable.

I had brought a couple of copies of the aerial photo I had taken of Aconcagua, and I set about writing a high altitude postcard that I had been thinking about writing. My ungloved hand still hadn’t quite frozen after this, and I managed to scribble a few lines on the back of the second photo before hurriedly having to put my mitt back on. I decided that getting two postcards written at 6960m was pretty good going, given that I seldom get round to writing them even at sea level.

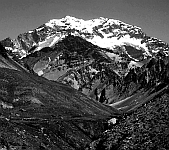

By this time I felt sufficiently rested to be able to get up and inspect the view. There was plenty to look at, especially to the south, where a number of 6000m peaks, including the distant pyramid of Tupungato, were clearly visible. Much of the view, however, was relatively uninteresting simply because, apart from the immediate foreground, everything was so far away or so far below. It was just like the view from an airliner crossing the Alps at cruising altitude. One interesting thing I detected, however, was that the uninterrupted western horizon had a slight but definite curve to it – the Earth wasn’t flat after all.

The guided group was there. I congratulated the Chilean guide on her precise prediction of how long the Canaleta would take us, and she gave us hearty congratulations for having made it to the summit. She was actually one of two Chileans who were guiding the six clients. Her companion had a handheld radio with amateur channels, and he had just made contact with an amateur radio operator in Viña del Mar on the Chilean coast. The ham sounded understandably excited at this contact, and passed his congratulations to all those present. I continued chatting to the Chileans for a while, and then noticed that cloud was starting to materialise to the west of Aconcagua.

I normally disapprove strongly of having my own camera pointed at me, but reluctantly I decided that on this occasion I would have to make an exception.

Cloud was building rapidly and starting to float between the main summit and the south summit, so there was suddenly a bit of urgency to get our pictures taken. In the end the summit photos we took of each other with the other’s camera were somewhat cloudy, but the sun continued shining on the summit itself throughout.

Dan was a little concerned about the cloud, because he associated cloud with high wind. However, this cloud was floating past very gently, and was probably just indicative of some moist air that had come up from the coast during the day. Later the clouds descended to a lower level, leaving the summit clear.

As it was now 5pm we had more or less discounted the possibility that Jim was still on his way up. All the people whom we had seen a little way behind us at the col had long since arrived on the summit. The Chileans were already leaving with their six charges – they had to make it all the way down to Nidos.

We decided to wait fifteen more minutes and then start the descent. We could see a group of four people a short distance below the summit, but Jim didn’t appear to be among them. One or two more were down by the col, but they were going so slowly that it wasn’t even obvious if they were coming up or going down.

I was feeling rested, but very feeble. The sensation was similar to that which one feels upon getting up after being bed-bound for a week. I could make myself totter weakly around the summit triangle, but the only position that felt natural was sitting down, and this was what I subconsciously did unless I was forcing myself to do something specific, like taking photos.

Our attention was suddenly caught by some strange noises coming from the direction of the aluminium cross. It turned out to be the sound of the Virgin Mary being venerated feebly and incoherently in Portuguese, to an accompaniment of fervent sobbing. Four ashen-faced individuals had just finished clawing their way on to the summit plateau. The Brazilians, it appeared, had finally arrived. Within a remarkably short space of time they had composed themselves : a Brazilian flag and cheesy grins were quickly produced for their summit photo.

We had just bidden farewell to the summit, and were actually starting the descent, when Dan suddenly announced that he thought he could see Jim down near the col. It was someone in a red jacket, using only one ski stick (everyone on the mountain used two except for Jim). Dan said that if it was Jim then he should really wait on the summit until Jim arrived. I was ready to head down at this stage, so we agreed that I would go down and see if it was Jim. If it was, then I would make sure he was OK, and tell him that Dan was waiting for him on the top. We arranged a couple of semaphore signals so that I could let Dan know what the score was before I carried on downwards.

It was just after 5:15pm when I left the summit, and in a little over five minutes I had got far enough that I could see that it was indeed Jim, albeit an extremely tired-looking Jim. His face was even whiter than the Brazilians’ faces had been. He claimed he was OK, and I said that he would probably be on the summit in a little over half an hour. I thought about suggesting that he not spend too long up there, and that he and Dan start down at 6pm whatever happened, but in the end I just let him go on. His progress was painful to watch – he was stopping every few paces to lean on a rock. I estimated that at that rate he would be over an hour getting up, but I thought this news might be too depressing for him. In any case Dan was above watching him, and was fit enough to come down and help if necessary. I gave the semaphore signal to Dan that we had decided would mean that it was indeed Jim, and that Dan should wait on the summit. I then turned downhill.

The ski sticks were invaluable on the way down – it was like having four legs instead of two. Even so, a few minutes down from the col I felt totally exhausted and had to stop for a rest. Getting going again after the rest was extremely difficult. I sat there feeling feeble for a while, waiting for enough strength to return to be able to continue down the rather steep section immediately in front of me. I knew that I would need plenty of leg strength to avoid slipping. Eventually I realised that the required feeling of strength wasn’t going to come. I would just have to somehow adjust my manner of descent to compensate for the fact that every muscle felt as though it had about a quarter of its normal strength.

I picked my way gingerly down into the top of the Canaleta, feeling very unsteady and rather vulnerable. I passed one chap who was sitting on a rock looking exactly as I had felt when I had stopped. He was sitting there looking a little dazed, patiently anticipating the return of his strength; he was waiting for the train the never comes – just as I had been.

All the way down the Canaleta I had to fight back the instinct to stop and rest – I knew that resting wouldn’t make me feel any better. So long as I didn’t go so fast that I was out of breath there was no point in stopping. Despite the feeble manner in which I was descending, I was losing altitude at five times the speed that I had gained it, and was soon past the dog-leg in the Canaleta. In front I could see what looked like the Chileans with their group, moving slowly but steadily.

Sure enough, thirty minutes later I had caught them up, just as they were crossing the top of the Gran Acarreo. I pottered along a little way behind them for a while, moving rather more easily than I had been. I was still having constantly to resist the temptation to sit down. I finally overtook the group at the Independencia hut : they stopped for a brief rest, all apart from Patricia (as she was shortly to introduce herself). She followed me down, and soon caught me up. The remaining hour of the descent felt much less wearisome : breathing was noticeably easier down here at 6500m. Also, having someone to talk to took my mind off the constant entreaties from my legs that I sit down for a few hours or preferably days. The fact that, for Patty, this was all in a days work was most contagious. Trotting down to Berlin Camp, chatting to her, suddenly made the descent of Aconcagua feel rather like the descent of… well… Catbells on a summer evening, perhaps. (Catbells is a famously easy and much derided hill in the English Lake District). Nevertheless, had I known that my new acquaintance, Patricia Soto, was destined to become, exactly 40 months later, the first South American woman ever to reach the summit of Mount Everest, then I might not have felt quite such a moral obligation to keep up with the blistering pace she was setting!

On reaching what it had earlier deemed to be 6000m, my watch altimeter suddenly started working again – it seemed none the worse for its adventures outside its design range. Berlin Camp appeared below us, and there seemed to be nearly twice as many tents as there had been in the morning.

I was pleased to be arriving, though the thought that I would shortly have to get stuck into such chores as melting snow did rather dampen the pleasure. Soon after 7:15pm, exactly twelve hours after departing, and exactly two hours after leaving the summit, I sat down by the little hut that had been home for the last three days.

Presently the rest of Patty’s group heaved into view. We said our goodbyes and off she went to lead them the rest of the way down to Nidos. The phenomenon of not being able to identify people who you know, when they are dressed for the summit, operated in reverse in the case of Patty. When I later saw her in Santiago, the only things I recognised were her voice, her mouth, and the end of her nose!

I sat outside the familiar refugio for a while longer – hoping that I might suddenly feel energetic enough to get some snow and start melting it. As before, the feeling didn’t come, but the temperature started its daily nose-dive. I thus had little choice but to get stuck in to camp chores.

It transpired that Jim had packed up the MSR stove before leaving that morning, so I had to work out how to put it together again before I could even think about melting the snow I had collected. There was no liquid water left anywhere, and it was very difficult to persuade the snow to liquefy, instead of simply sizzling into steam. Eventually the snow co-operated, and by 8:30pm I had both Jim’s cooking pots full of boiled water.

I still didn’t feel remotely hungry, but a cup of tea was a different matter. However, I couldn’t find my sachet of dried milk, and after some searching it was clear that someone had been in the hut helping themselves to our food. My remaining biscuits, crackers, and mashed potato had also disappeared. I was only mildly peeved, as for a start I wasn’t hungry, and secondly we had benefited enormously from the food that someone else had left. Even so, there was no excuse for someone to have come in and helped himself to food in an occupied hut.

I checked if there was anything else missing, and for a short while was unable to locate the little bag that contained my short-wave radio and exposed film. It was interesting that in the five minutes that elapsed before I eventually found the bag, I was only moderately irritated. The radio was inconsequential because it was replaceable, and even the exposed film didn’t annoy me anything like as much as it normally would have done. No doubt the reason was simply that at that moment nothing mattered to me other than the day’s achievement, and nobody could possibly steal that from me.

There was no sign of Dan or Jim yet – in any case I didn’t expect them to be back much before nightfall. I noticed two Brazilians in the nearby tents peering upwards every so often, so clearly their more successful summit-conquering comrades hadn’t come back either.

At 9.15pm it was already getting gloomy and I started to wonder what, if anything, I should do if Jim and Dan hadn’t arrived by nightfall. I quizzed an Argentine who I had seen arrive twenty minutes earlier, and he said that he had passed two people in red somewhere above the Independencia hut. He said that they had been going very slowly.

By 9:30pm it was dark, and I made a rather alarming discovery in the hut. This time it wasn’t something that should have been there and wasn’t. It was something that shouldn’t have been there and was : it was Dan’s head torch. Coming down from Independencia in pitch dark with only one head torch between two would be slow and dangerous.

The worrying logic was that if Jim had known that he should take his headlamp, then he would have told the inexperienced Dan also to take his also. Dan hadn’t taken his light, ergo Jim probably didn’t have his either. If it were the case that neither had a torch, then trying to descend any part of the route above Berlin Camp in the pitch dark would be somewhere between impossible and suicidal.

At 10pm it had been pitch dark for half an hour. I very reluctantly decided that it was time to put my boots back on, and head uphill once more.

Way cool picture, Malcolm. You should definitely consider it for the cover of your next album. No offence, Dan, but your picture, not so much…