A kilometre after the Argentine border checkpoint the bus pulled into the side of the road at Puente del Inca, and off I hopped. The bus driver’s assistant elected to heave my rucksack out of the luggage compartment for me, and then probably then wished he’d left me to do it.

I made some inquiries in the little shop and was told that there was a refugio round the back, with bunk accommodation, where most of the trekkers and climbers stay. I found it and it was just like simple youth hostel in the UK (or rather like simple youth hostels used to be in the days of real hostelling/hostellers). There were two or three foreigners around, but I got chatting with some very welcoming Argentines (including the owner) in the kitchen, where they were all drinking yerba mate (strong tea drunk from a gourd through a metal straw).

They gave me some rough details about the current state of things on the mountain – the first recent information I’d received about actual conditions. Apparently people had been returning from successful summit bids within the previous few days. This was quite a relief, as I hadn’t been sure what effect El Niño was having or had had on the snow conditions. Even though mid January is normally the ideal time to climb Aconcagua, I had been a little worried that on arriving at Puente del Inca I would be told : “Aconcagua!?! Forget it! There’s still ten metres of snow at Plaza de Mulas – try again in two months..”.

In the dormitory I got chatting to two Australians : Tim, a friendly easy-going guy of about my age, tall and wiry; and Tork, who was a little older and more reserved – an interior decorator who normally lived in the UK. They appeared to have met “on the road”. Tim was at the end of several months touring Latin America, and had just hired virtually all his mountaineering gear in Mendoza, including his boots and his tent. Tork had brought everything from the UK and was heading on to Australia afterwards. They both seemed to have prepared well for Aconcagua, and appeared determined to reach the top.

I wandered down to have a look at the famous natural bridge. I was already noticing the effects of altitude, even though I was only at 2700m / 9000ft. However, it was good to know that the acclimatisation process was now in full swing. When I got back to the refugio I got talking to an American and his young British companion. At first this pairing seemed unusual, but it quickly turned out that Jim was Dan’s boss. Jim, forty something, owned an outdoor sports training camp for kids in California, and Dan, a twenty year old student from North Yorkshire was one of his prize instructors – a champion mountain biker. Dan hadn’t brought his bike, and in fact was new to mountaineering. Their trip to Aconcagua seemed to be the result of over a year of planning. It was all Jim’s idea : he appeared knowledgeable and confident about all aspects of Aconcagua. He later admitted having done huge amounts of meticulous research in preparation for the trip : after a while I couldn’t help but wonder how much of his mountaineering knowledge came from this, and how much came from actual high altitude experience. He had obliged Dan to follow all manner of strict regimes in preparation, including no alcohol for several months. Dan privately admitted being more than a little cheesed off with this puritan lifestyle that his boss had imposed, especially when I said that it never would have occurred to me to stop drinking alcohol prior to the trip, and didn’t see what the advantage would be if any. Jim had a sophisticated water filter which he had insisted on using even at Puente del Inca, where the tap water is treated and perfectly drinkable (as it generally is in the rest of Argentina).

Later we all ate the standard meal offered by the refugio, at the same table, together with a young Argentine couple who’d been off trekking in Los Horcones valley. I ended up doing some simultaneous translation, which was amusing – Jim had a smattering of Spanish, and the Argentines about the same amount of English. At one point Jim was talking about mountain bikes, basically in English, but throwing in a few Spanish words that he knew, or thought he knew. It could be that in some countries mountain bike is “bicicleta de montaña” but in Argentina mountain bike is “el mountain bike”. So when Jim, speaking in English, threw in “bicicleta de montaña”, I automatically translated it back to “mountain bike” in my simultaneous Spanish translation to the Argentines, which caused everyone to roll around with mirth.

Later on we sensed a buzz of excitement outside, and two rather grubby and very tired looking Irishmen entered the room, having just arrived at the refugio. Yes, they had just come back from Aconcagua, after successfully reaching the summit; after a respectful pause, Dan and I quizzed them for some information.

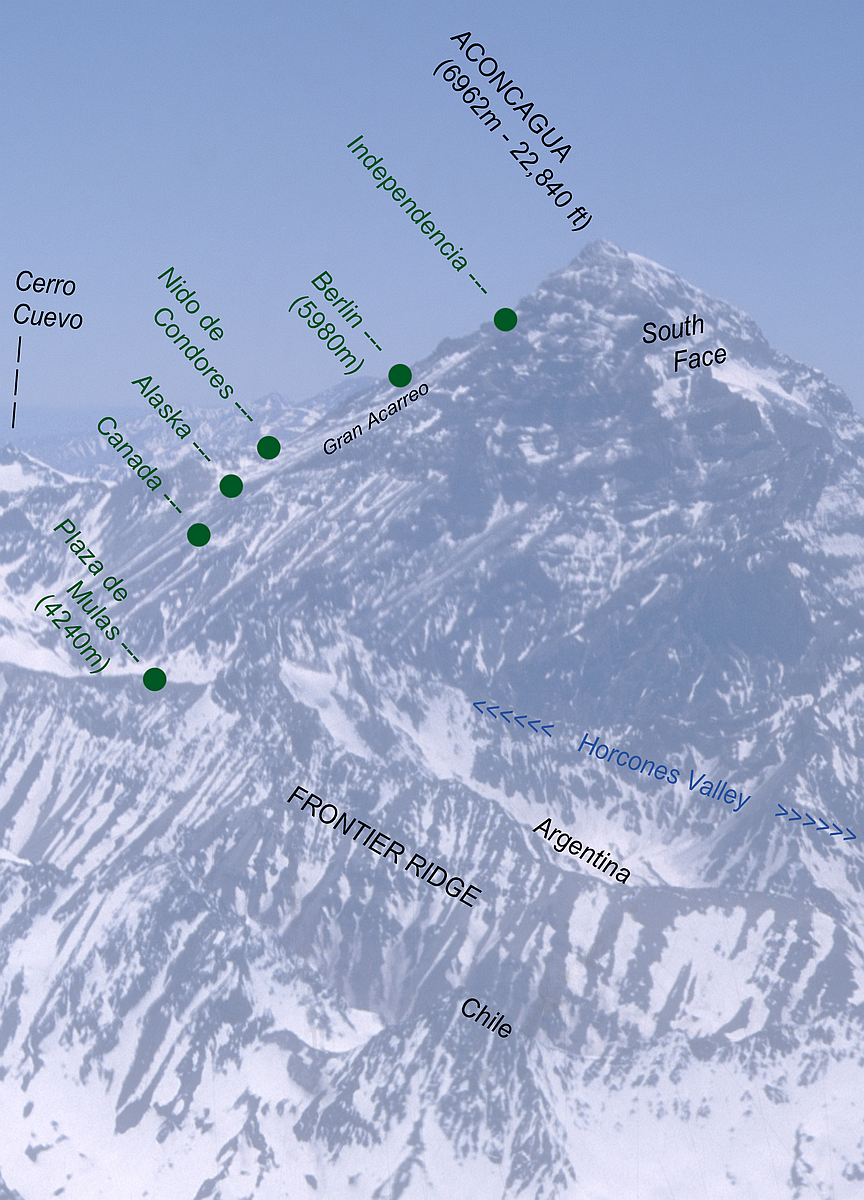

They had made their summit bid from Nido de Condores camp at 5400m, and had in fact come all the way down from there in one day : quite an achievement. They reported good conditions on the summit, but that several people had developed pulmonary oedema (a dangerous lung condition) at or near base camp at Plaza de Mulas (4400m). They seemed to think the key to a successful acclimatisation was to spend three nights at Plaza de Mulas. Most people they had met who had suffered little or no AMS (Acute Mountain Syndrome) had spent several rest days there, whereas people who had gone up to Canada camp at 5200m too soon had generally had problems. They described to us the infamous Canaleta, and gave us some hints how to cope psychologically with the final thousand metres. The said that the two of them had been in such a deteriorated state when they finally reached the summit that they almost forgot to take any photos. They said, in short, that they had found the whole trip exceptionally tough and that they had no desire whatsoever to repeat the experience!