I woke several times during the night, feeling short of breath, which didn’t seem a very good omen. I felt no urge to hurry in the morning. What was ultimately going to govern the length of the trip was how fast I could acclimatise, and today 9th January I was acclimatising just by having a pleasant lie-in at 2700m. I chatted some more with the Irish guys, one of whom turned out to be a senior employee of the company that makes Therm-a-Rest mattresses in County Cork. One rather worrying thing they said was that there was no chance of getting tent pegs into the ground anywhere. They also expressed concern that I wasn’t planning to take ski-sticks with me – they said it was almost essential. I had never felt the need to use sticks, apart from in the Cairngorms in Scotland in 1997 when I had a bad back, so I hadn’t thought of getting any. The Irish guys said I would waste a lot of energy in the Canaleta without sticks, and offered to sell me one of the pairs they had used, for a very reasonable price.

Jim and Dan were going to wait a third day at Puente del Inca to acclimatise further (much to Dan’s privately expressed disgust), and were intending to send their excess gear by mule. They weren’t going to fill the mule (each mule takes up to sixty kilos at a cost of $120 each way) so in theory I could have shared some mule space with them. However I had already decided that if I could physically stagger around with thirty-five kilos on my back I would make do without help from a mule, even if it meant taking an extra day to reach Plaza de Mulas. Acclimatisation dictated that there was no advantage in rushing to Plaza de Mulas. People usually take two days if they use mules for their gear – I was planning on three days without a mule. Tim and Tork were planning on taking three days even though they had used a mule.

It was a warm day, with brilliant sunshine, so I wandered down to the natural bridge again to take some photos. The place was rapidly becoming overrun by day-trippers from Mendoza, including a busload of boisterous schoolkids.

I’d been worried about the fact that I wouldn’t be able to use tent pegs, since my tent relies heavily on being well pegged to stay up, especially if there is any sort of wind. I didn’t have enough cord to make loops to tie round rocks at the pegging points, but I managed to buy six or seven pairs of white nylon shoelaces from the little shop by the roadside.

Back in the refugio I tied the day sack on to the top of my rucksack (along with several other things that had to be tied on such as my waterproof jacket, crampons, ice axe, and new ski sticks). I then made an attempt to heave it on to my back. Attempt number three was successful, but left me without any great desire to repeat the manoeuvre. Once it was on, walking around was easy enough. I said “see you later” to Jim and Dan, and was off, hoping that I still had enough daylight to reach the first camp site, which was 15 km away at a spot called Confluencia.

The first kilometre was road bashing; a path then headed off up to the right to bypass the customs/immigration building, and provide a short cut to the park entrance in Los Horcones valley. Although my legs were carrying well over 50% more weight than normal, all the relevant parts of my body seemed to be working satisfactorily, and the rucksack wasn’t too uncomfortable. It was tremendously satisfying to think that I was carrying everything that I would need to survive sixteen days away from civilisation, coping with temperatures anywhere from +30C to -30C, and, in theory at least, to reach nearly 23,000 feet without any assistance from anyone.

The sun was very strong and I soon had to stop to take off my fleece jacket. To paraphrase another saying concerning shoelaces and age : “you can tell when your rucksack is too heavy if when you take it off you wonder what else you should be doing while it’s off”. In this case I gulped some water and took a photo of Aconcagua, which had just come into view round the corner of the entrance to Valle los Horcones.

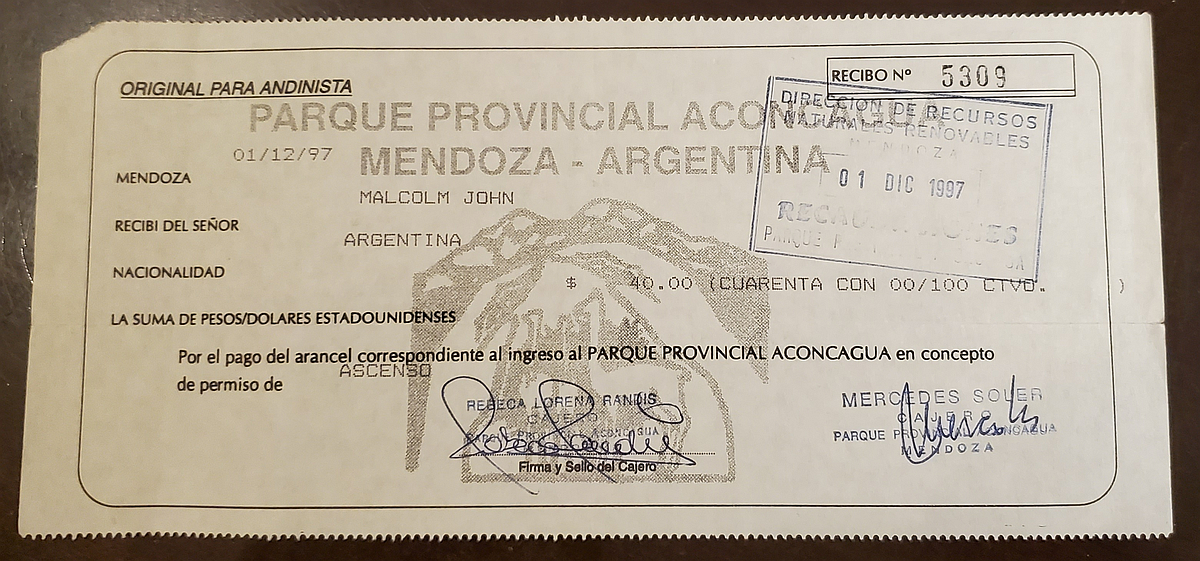

I headed up towards the park entrance – there was a new chalet-style tin roofed building that wasn’t quite finished yet, and a tent with “guardaparque” written on the side. There were plenty of people milling around – one of the day trip buses had come up from Puente del Inca and was disgorging a rabble of teenagers. The guardaparque (park ranger) spotted me and came over from where he was working near the new building. Just at that moment an attractive young lady wielding a camera bounded up to me, announced she was a journalist, and asked if she interview me. A few questions consequently came my way concerning my intentions on Aconcagua, my past mountaineering experience, what I was doing in Argentina, and if there was anything that had caught my attention about the area. She was quite young and I assumed that she was just a student studying journalism, and had come out to do a survey on the types of people who visit the Aconcagua Provincial Park. Eventually the guardaparque, a pleasant chap who later introduced himself as Ariel, checked my permit, tore off the relevant part, and recorded some details of how long I expected to be in the park. He gave me a large numbered rubbish bag to take with me – mine was number 387 and I wondered if that meant that 386 visitors had entered the park before me in 1998.

Just as Ariel was handing me back my half of the permit, the journalist snapped off a couple of photos of us – I thought no more of the incident until I got down sixteen days later, and discovered that in my absence Ariel and I had become minor celebrities…

Topping up with water, I discovered that the extra half litre was almost the “last straw that broke the Malcolm’s back” : my first attempt to lift the rucksack failed completely. Ariel, the guardaparque, put out an arm to assist with the second attempt, thus saving me further embarrassment. Everyone wished me the best of luck, and off I plodded once more towards the shimmering white monster in front of me which, although still thirty-five kilometres away, already seemed to fill the sky…

The vehicle track that led from the main road to the park entrance continued up Los Horcones valley, and I began to hope that it didn’t go too far. Soon I came up to a small lagoon, where a number of the day-trippers had accumulated. A little further I decided that since the rest of the day was going to be an uphill slog I should really top up with some high calorie food. So off came the rucksack again, and I tucked into a couple of squares of the first of four enormous rum and raisin chocolate bars that I had brought for the purpose.

A few clouds then started appearing and after I had been walking for another thirty minutes most of the sky had completely clouded over. I heard the sound of a vehicle behind, and looked round in some annoyance to see a minibus bumping along the track. It caught me up and then stopped. Some people set up a video camera on a tripod – I spoke to a couple of the people and they said they were journalists. They didn’t actually film me though, and I didn’t see the girl who had interviewed me before. I left them behind, hoping that I would not be passed by any more vehicles. Thankfully the vehicle track soon descended to a large footbridge over the river, and that was as far as it went. The bridge had obviously been designed to be comfortably big enough for mule trains, but not for vehicles. In any case there was just a footpath on the other side, which followed the east bank of the river.

Over I went, and after a while people started to pass me going down. I saw at least fifteen during the afternoon, and once or twice I asked people how far it was to my first camp site at Confluencia. At one point, soon after the bridge, there was a confluence of rivers, with several excellent places to camp, and I for a moment I thought to myself : “Wow, that was easy!” Then it was obvious that it wasn’t Confluencia after all.

The valley steepened after another couple of kilometres, and there were some impressive precipices up to my right. By mid afternoon the wind got up (a headwind of course) and it started to rain a little. I crossed with the last of the day-trippers, a group of wide-eyed teenagers who were hurrying down a little anxiously. One little group of them paused to quiz me, and to tell me it was raining hard at Confluencia. One girl asked if I was going to the summit, and when I said I was, she said in an exasperated voice : “Aren’t you scared?!”. Clearly she had already gone as close to Aconcagua as she considered prudent.

Eventually the ground fell away to a fast flowing river, and it was clear from the lie of the land that this was the real confluence. A flimsy bridge crossed the torrent, and some paint on a rock told me to go left to get to Confluencia camp. Ten minutes later I was round in a sheltered valley. At least a dozen tents were clustered on the west side of the other branch of the river, the branch that I presumed came down from Plaza de Mulas. I crossed the stream, said hello to the guardaparques, and then found a rocky but flat pitch thirty metres beyond the guardaparques’ tent. There was a bit of a wall built on the uphill side of my pitch, which was fortunate as the wind was gusting from that direction. I was more than a little concerned about the fact that I wasn’t going to be able to get any pegs into the ground.

As it turned out, I did get a few pegs in, but I was still heavily reliant on my fourteen newly purchased shoelaces. After a couple of false starts, I discovered the best way to employ them : tying one end to the pegging point on the tent, and create a loop with a slip knot at the other end.

One rock went in the loop, which was pulled tight, and then another rock placed on top of the shoelace close to the tent. Once the first rock was pulled away from the tent to provide some tension, the result seemed to be as good as a tent peg would be. Once a further three or four rocks had been piled on top of the first two, I was sure that it was more secure than a tent peg. This was a good thing too, as by all accounts the winds higher up were going to be fearsome.

While I had been putting up the tent it had continued raining slightly, and when it stopped I wandered round the campsite. I found Tim and Tork, the two Australians, and we chatted a while. Looking up at Aconcagua it looked as though Confluencia was a good place to be. An enormous cloud clung to the mountain, and the whole of the upper Los Horcones valley seemed to be getting a good soaking. It was all very different from the morning’s perfect conditions, and served as a reminder, if one were needed, of how fast conditions can change. A hailstorm suddenly descended on Confluencia camp, and I went back to my tent to shelter and heat up some soup.

Later on, I poked my head out and saw that the cloud had partially cleared from the very top of Aconcagua, which was starting to gleam a brilliant orange colour in the setting sun. I fished out my camera, and as the cloud gradually melted away from Aconcagua the summit turned pink, making a photo imperative.

I had originally bought only two rolls of camera film (of 36), in order to try to stop myself being snap-happy. But then I had bought a third film when I remembered what had happened when I had visited the Mt. Fitzroy area three years previously (I ran out of film in one of the most spectacular locations I had ever been). As it turned out, if I had taken 5 rolls to Aconcagua I would have shot the lot.

A group with a guitar a short distance away started playing and singing – there were several sizeable groups of people around, including thirteen French Canadians, who I was to get to know better later. I knew that I should try to be sociable in order to find people to team up with, but I felt very tired and soon crawled into my sleeping bag. I had brought my little Sony short-wave radio with me, but I was too deep in the valley to pick up anything, and I soon fell asleep.

Hola Malcolm. ¡Súper interesante el relato! Lo encontré ayer en facebook y hasta hoy me puse al día. ¡¡Espero ansiosa el resto!! Ayer escuchaba en la radio que ya no se puede bajar en Puente del Inca por temor a que esté “flimsy” y provoque algún accidente.