The next day (12th January) being a rest day I felt no guilt in staying in my tent until well after the “9:15 instant warm-up”, and in fact only got up because it got too warm. The Australians were likewise lazing around. A leisurely breakfast paved the way to a lazy morning of idle chat, as we lounged around outside Tim’s tent.

As the day drew on we discussed what our movements might be during the next week. We reckoned that our one day of complete rest at Plaza de Mulas (4400m) would keep the acclimatisation ticking along nicely. The rough plan then seemed to be to take four days to get everything up to Nido de Condores (Condor’s Nest) at 5700m, and after another rest day there, have an attempt on the summit. We got the impression that most people who had made the summit had done it from “Nidos” (as it was called amongst the foreigners) rather than the higher Berlin Camp. The problem with Berlin Camp was that it was just within the “death zone”. At or above 6000m in the central Andes the body doesn’t acclimatise but just gradually deteriorates. Apparently in the Himalayas the level at which the death zone starts is several hundred metres higher. The result of Berlin Camp being in the death zone was that too long spent there could render us incapable of reaching the summit, even though we would have less to climb than from Nidos.

The sun was very powerful and I felt even my hands burning – normally I wouldn’t bother to put sunblock on them. The air was cold, however, so the perceived temperature depended entirely on the wind speed. There was therefore a wide difference of opinion concerning what was the appropriate attire for Plaza de Mulas. There were people briskly walking around with duvet jackets on, apparently not suffering from overheating, and there were we just sitting still in T-shirts, and feeling hot in the blazing sun. In the end I had to put on my woollen hat to try to stop my head from overheating or burning.

I had a look through a book on Aconcagua that Tim had brought with him, a book that several other people had also brought. It was essentially a series of pieces written by different members of an American group that had come out to climb Aconcagua. There was a useful section giving general hints to readers wanting to climb the mountain themselves, but the bulk of the book consisted of the memoirs of each person. The text was arranged with a paragraph written by one person followed by a paragraph by the next and so on. It was rather confusing to try and follow. In the small amount that I read, I got the impression that the people on the trip had been brought together in a rather impulsive and haphazard way. Some of them seemed to have been on the mountain only as a result of peer pressure. The trip didn’t seem to have been at all successful – there were diagrams showing that X got to this point, Y turned back here, this is where Z had his accident, and so on. Only a fraction of the group actually made it to the summit. The upshot was that a group that had set out full of exuberance, confidence and high expectations, went home to the USA with its collective tail between its legs, having found Aconcagua a great deal more serious than anticipated.

As I sat by Tim’s tent, leafing though it, I wondered why such an unsuccessful expedition, of which so many members had failed to make it to the summit, should have produced a popular book that people were now using like a guide. The answer, as I was to discover during the subsequent ten days, was that the experience that these Americans had had was all too typical. At the time that I sat relaxing by Tim’s tent, I was under no illusions about how serious 6960m would be for me. However, I still imagined that if I did make it to the summit, then I would be up there in the company of practically all the twenty or so people who I had met on the way. These twenty, and many more besides, were all currently sitting here in Plaza de Mulas just as we were, happily planning their ascent strategy, looking forward to their summit day, or perhaps just resting. We would make quite a crowd on the summit, I thought. I still hadn’t appreciated that it was highly probable, statistically speaking, that the majority of us would ultimately be given the thumbs down by Aconcagua and return home without a summit photo…

A late breakfast meant that lunch was a simple affair. Then the clock worked its way round to 3pm and the highlight of the day : the $10, five minute, hot shower. Tim had the earlier appointment, and came back looking most refreshed (though that’s not what I told him at the time). Then it was my turn, and up I went to the metal hut known as the EcoToilet. This had been set up by an enterprising young Argentine who had clearly seen the chance to make a fast buck out of rich and smelly gringos. The system was solar and wind powered, with four tanks soaking up the sun’s rays, and a windmill to generate power for the pump. The guy in charge said that he could get about fifteen showers per day out of the system, which clearly translated to a healthy profit during the climbing season, given that the running costs were minimal. It was clean, and there was plenty of hot water. The time limit wasn’t imposed, and in any case five minutes was plenty for me – I even managed a shave. The EcoToilet also contained proper flush toilets which could be used for a one off payment of $10. The idea seemed to be that a small amount of the warm water from the solar tanks was used to encourage the sewage to decompose. This is something it doesn’t do in the pit latrines that have been dug in various strategic locations round Plaza de Mulas. The system may or may not have been more ecological than the latrines, but it was certainly no less smelly. In any case I decided against further patronage of the EcoToilet.

The leisurely afternoon continued – later on we saw Jim and Dan arrive in their matching trendy red North Face jackets, and then wander around Plaza de Mulas looking rather lost. Eventually Tork went and found them and they reported that they were knackered. Later on still, we saw Smiler return from higher up the mountain, and the Australians went to ask him if there was a water supply at Canada Camp. He said there wasn’t, but seemed reluctant to share any more information – we wondered if his client was getting jealous of him being helpful to people who hadn’t paid him to be helpful…

One of the girls from the French Canadian group stopped by for a chat and said that their plan was to go all the way to Nido de Condores at 5700m the next day to carry food up. This would be the first of three trips to Nidos for them – they intended to make two carries to Nidos and then take their tents up. In theory they were saving a day compared with our plan, but the idea of doing the same ascent three times on three consecutive days didn’t appeal to us.

Hunger eventually returned, and we all decided that two of Andrea’s cheeseburgers were exactly what our stomach craved. But alas, Andrea was just heading off somewhere, and we had to wait for half an hour. I climbed a little way above Plaza de Mulas to take some photos looking down on the mass of little tents.

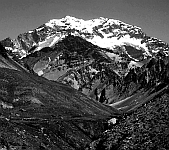

Then the thirty minutes was up and we reconvened at Andrea’s tent for our evening meal. This time she offered cups of tea afterwards, still included in the price. Reluctantly we headed back to the relative discomfort of our own tents. By and by the west face of Aconcagua blushed orange and then pink, and a few photos had to be taken.

The cloud had built up much less that day, which seemed to bode well for the next days “carry” to Canada Camp at 5200m. In going to Canada I would be breaking new ground in terms of altitude. The highest point to which I had ever previously climbed was the summit of Tungurahua in Ecuador, at 5016m (I had been by bus up to 5200m in Bolivia, to the Chacaltaya ski station, but this seemed much easier at the time, as I had been at 4000m for two weeks previously – and in any case “bus ascents” don’t really count).