A couple of km further on I passed the ruins of a brick built refugio – it wasn’t obvious why it had been so badly damaged. I could only assume that it had been crushed by a mud slide, or rockfall, or perhaps by exceptionally heavy snow. The path started to zigzag up the steep slopes on the east side of the valley. After half and hour I halted to cool off and have lunch. A group of half a dozen soldiers came up past me and paused briefly for a chat. The military appeared to have their own base camp slightly below the main base camp at Plaza de Mulas. Another hour further on the ground levelled off, and I asked someone coming down how far it was to Plaza de Mulas. “Less than five minutes” was the reply, which I didn’t believe as I couldn’t see any tents anywhere. Ten paces further up, however, I came over the top of a slight rise and suddenly saw over seventy tents spread in front of me. They occupied a gently sloping area of rocky ground with a series of small ridges and gullies.

The two Australians had pitched their tents near the centre of the area, just below the guardaparques tent. They were lounging around outside their tents, looking very relaxed. It was only 3pm, the sun was still very strong and there was no wind. It was wonderful to finally take my rucksack off, as from there on I would be ferrying things up the mountain – the days of carrying thirty five kilos in one go were over. I went up and reported to the guardaparque (compulsory at Plaza de Mulas), and then pitched my tent next to the two pitches where Tim and Tork had installed themselves. It was again exhausting having to go and fetch the necessary rocks, but it was good to know that I probably wouldn’t have to repeat the operation for three nights.

Eventually it was done, and I sat down by Tim’s tent to rest. The Australians asked if I had seen the body bag on its way down. I said I had and asked if they had any more information about what had happened to the Japanese guy. They said that the version they had heard was that he was Korean, not Japanese, and that the body had been found a week after the chap went missing.

Tim announced that there were hot showers at the camp, together with places selling hamburgers. This all sounded rather good, but I suspected that these luxuries would come at a cost, commensurate with the location. Sure enough Tim later discovered that the shower cost $10 for five minutes and had to be booked in advance. Initially this seemed ridiculously expensive, however, after some thought, the prospect of being clean was so delightful that I later made a reservation for the following day, as did Tim.

The Aussies wanted to wander over to investigate the new refugio/hotel on the other side of the valley, and I joined them. It was over a kilometre away although it looked a lot closer. After half an hour we got there, and although cold inside it seemed quite comfortable – it was rather like a British purpose-built youth hostel, but with impressive snow defences on the outside. The prices were definitely not similar to a youth hostel : $15 in the unheated bunkhouse without the use of the washroom, $30 in the same bunkhouse with use of the washroom, and something over $120 per night for a room with meals included. They sold hamburgers, but at a higher price than in the campsite. Tim had noticed adverts for telephone calls at normal Argentine rates, and decided to ring his girlfriend in Australia. It was actually a single frequency short-wave radio, with a phone “patch”, and Tim had to tell his girlfriend to say “over”. It wasn’t very private – everyone in the lobby of the hotel could here both sides of the conversation.

We wandered back to the campsite, and so much talk of the price of hamburgers made us all unable to think of anything else. Therefore the only option was to go in search of the said items. There seemed to be two tents offering “fast food”. We decided that the best thing would be to try one and then the other, firstly to check which was best, and secondly to ensure full stomachs. The first place came up with the goods, and we each munched our merry way through a cheeseburger. The cost was $5 each, which wasn’t too bad really, considering the amount of pleasure derived. But we went to the second place with open minds, and half-full stomachs. There we were served our $5 cheeseburgers by the lovely Andrea, who not only smiled very sweetly at us, but also gave us a large jug of fruit juice included in the price. So after that there was no question about which place we would go to when hunger struck. In addition, Tim spied some packets of dried mashed potato in Andrea’s tent, and being short of this commodity persuaded Andrea to sell them to him. Encouraged by this trade, and being short of sugar, he later returned to her tent, together with his interpreter (me) and a large pineapple which he, or more precisely his mule, had carried up. He hoped to swap the pineapple for some sugar. Andrea, being a canny young lass, readily agreed to this deal, and elected to throw into the bargain (by way of a sweetener) half a jar of her mum’s home-made jam. Tim was ecstatic with the deal, as, no doubt, was Andrea.

Sitting back by the tents, we were greeted by a British-sounding guy who walked past, who seemed to go by the nickname of “Smiler”. Tork was surprised that I hadn’t recognised him – though when they said his name was Dave Cuthbertson the name did ring a bell. “Smiler”, they said, had become the most talked-about mountain guide in Britain during the previous few months. This was due to a questionable negligence law suit that had gone against him, thereby setting a precedent that could jeopardise the livelihoods of all mountain guides. The Aussies had met him at Confluencia, and he was with a British client, who seemed to have paid Smiler to accompany him all the way from UK to take him up Aconcagua. Given that I had simply packed a rucksack and hopped on the bus, I found it hard to imagine the circumstances that had led the client to do something like that. He must have been ludicrously well off, interested enough in conquering Aconcagua to go half way round the world, yet not interested enough to want to pit his own wits against it. He must have been keen enough about mountaineering to be prepared to endure the hardship of high altitude, yet totally unadventurous in his approach to the sport. I wondered if it could be that he moved in social circles where he would gain more points from having employed Dave Cuthbertson to take him to the summit of Aconcagua than he would from having made it using his own initiative. In fact, for all his Himalayan expertise, Smiler appeared a little lost. He knew no Spanish, had apparently never been to Aconcagua before, and seemed to know no more about the route up it than I did…

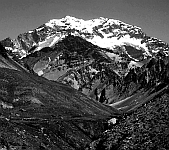

The temperature plummeted with the setting sun, and having admired the beautiful colours of the evening light on Aconcagua’s west face there was nothing for it but to quickly climb into my sleeping bag. This time I could just pick up the BBC World Service on my short wave radio, and listened for a while. The candle light was just enough to read by, and I re-read part of the guide to high altitude mountaineering – the booklet that had been issued with the Aconcagua permit. The translation was a little wide of the mark in places, but in general the author got the message across clearly and concisely. The guide indicated, basically, that all manner of strange and horrible things happen to the human body when it ventures above 5000m…