A steady strong wind would probably have made it much easier to sleep. The problem was that several minutes of silence was inevitably followed by an ominous whistle, the precursor of a vicious gust, whereupon I would wake up just as the tent suddenly started to shake. There was no real danger of the tent going anywhere. It was just annoying, and vaguely worrying given that however strong the wind was at base camp, it was going to be vastly stronger and more annoying higher up. Furthermore, my tent seemed to be making much more noise than anyone else’s. I didn’t know how many times I was actually woken up, but it seemed like hundreds.

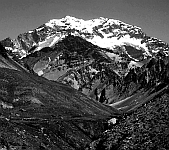

Shortly after 9:15 I peered outside. The view and conditions were different from the previous few days. The sky was still blue, but the temperature had risen slightly, and the wind was gusting enthusiastically. The most significant feature of the weather could however be seen by looking up towards the summit of Aconcagua.

An awe inspiring halo of cloud danced around the summit, all at once stationary and fast moving. The sun shone through the capering coils of cloud giving them all the colours of the rainbow. The effect was akin to that of an electrostatic “plasma” – it never looked the same twice, and would change appearance completely within a few seconds. One instant the summit would be wearing a helmet of milky-white luminescent cloud, like a mushroom head, all parts of which were streaming eastwards at unbelievable speed, yet the formation wasn’t moving. Then within five seconds this would miraculously dissolve into a cat’s-cradle of vortices, which would unite into an irregular pulsating halo draped around the summit. This halo would spawn wavelets of turbulence, which would pirouette eastwards at a couple of hundred kilometres per hour while the sun made them gleam the seven colours of the rainbow. Then the halo itself would buckle and cave in on itself, collect its kaleidoscopic fragments, and once more build up the milky white luminescent mushroom-head to cover the summit again.

Clearly the jet-stream had come down below 7000m – the summit was currently out of bounds to human beings.

This didn’t really matter just now – I was content just to watch the spectacle. However, our intention that day was to reach Canada Camp and stay there, and with this wind we were in no hurry to strike camp and head up to a site that we knew to be exposed. After breakfast we resumed our familiar “conference position” around Tim’s tent. Looking up to the boulder slopes above, we could see a few people struggling uphill. The dust they were kicking up seemed to be going at a very uncomfortable speed. We resolved to wait for a while to see what the weather would do.

During the morning the wind at basecamp subsided a little, but was still annoying by the way it would suddenly appear from nowhere. Looking at my tent I noticed that the rocks I had put along either side of the flysheet between the centre and foot-end pegging points hadn’t really done any good. The tent had just lifted free of them. I wondered what I could do – this seemed to be a major source of flapping, and a point where the wind could potentially get under the tent and rip the whole thing to shreds.

Towards mid-day, Tork announced that he was changing his plans slightly. He was going to ascend with an empty rucksack and pick up the food he had left at Canada. He would then take this up to Alaska Camp at 5500m, and then return to base camp to sleep. In the morning, all being well, he would go straight up with his tent to camp at Alaska. This sounded a sensible plan, especially for Tork who couldn’t really afford to waste another day at basecamp doing nothing. Tim and I reckoned on waiting until the afternoon, hoping that the wind would die down, and then if at all possible go up to Canada as planned. Failing that we were going to go up the following morning, pitch at Canada, and in the afternoon do the carry to Nidos as originally planned, returning for one night at Canada. We watched Tork slowly disappear up the zigzags, accompanied all the way by his plume of high speed dust.

After some lunch, I looked again at the problem of my flapping flysheet, and decided that after eighteen years, my tent deserved an upgrade. I removed the two shoe laces that were tied to the rear pegging points of the inner tent, and replaced them with some ordinary string that I had brought with me. The two front pegging points of the inner tent already had just string, as the inner didn’t need to withstand much force. Next I chopped the two nylon shoe laces in half and melted the ends. Then I sewed the four half-shoelaces to the bottom of the flysheet. I put two on each side, at equal intervals along the section where the wind was getting under the tent. I fetched a few more rocks to hook into the new loops, and once I was finished whole thing was a lot more secure.

The wind seemed to be easing slightly, and the vortices round the summit were dancing less energetically. We dithered about whether to go up or not. The rumours were of a forecast for three days of high wind at the upper camps. While there was no tearing hurry, we had no desire whatsoever to spend three more days in Plaza de Mulas. Tim wandered around and talked to a few people who had come down from Canada. He came back and said that the collective opinion was that : yes, it would be nasty at Canada, and even nastier higher up, but the place to wait for good weather is not Plaza de Mulas : at some point you just have to take the bull by the horns. We struck camp.

I swapped my trainers for my plastic boots. I had tried out the boots in my flat in Santiago, and had briefly put them on the previous afternoon : now I just had to hope they would be OK. I stuffed my trainers into a bag together with my rubbish and a days worth of low altitude food, and then took the bag up to Andrea’s tent. We returned to where our tents had been, and heaved our rucksacks on to our backs. We were ready to bid farewell to Plaza de Mulas.

We squeezed through the penitentes just like the previous day, and headed uphill. The best part about plodding once more up the zigzags was knowing that today we were doing it “for real”. We wouldn’t be returning to Plaza de Mulas this time – we would be spending the night camped on a small ledge on the side of the highest mountain in the Andes. It was quite a thrill…

After ten minutes we met Tork coming down. He had completed his mission and had left his cache at Camp Alaska at 5500m. He was surprised to see us heading up so late, even though we would have plenty of time to arrive and pitch the tents before it got dark. He said it was windy but not unbearable higher up. He said he would see us the following day at Alaska or at Nidos.

The wind continued to abate, and I suddenly felt delighted not to still be dithering down by the tents in basecamp. After an hour we had a rest, slightly below where I had stopped the previous day. Another easy hour of ascent got us up to Canada, where the wind was occasionally gusting, but as Tork had said, not unbearable. There were six or seven tents already pitched there, including Dan and Jim’s. We also found Smiler and his client, along with a half American half Argentine acquaintance of Smiler, who was also a guide. This friend was telling everyone that he had had to take someone down that afternoon who had pulmonary oedema, and had run back up again. His manner was far from reticent – we had noticed him in Plaza de Mulas wearing an incredibly loud pair of knee length shorts, that might have looked normal on the beach in Hawaii, but not at 4400m in the Andes.

I immediately began putting the tent up. As expected it was very exhausting, and to make matters worse, the wind seemed to be getting up again. Once the tent was up, but not yet properly secured, I found myself breathlessly rushing around to get rocks into the right places to stop it blowing away. By the time it was more or less secure, I was certain that putting up the tent had exhausted me far more than the climb up there had done. I was pitched right next to Smiler, and as I worked I could hear him recounting to his client anecdotes about some Himalayan or Alpine exploits of days gone by, throwing in a few famous names every so often. I heard the names Pete, Joe, and Al mentioned more than once – I assumed that he was talking about the late Pete Boardman, Joe Tasker, and Al Rouse. Perhaps having these anecdotes recounted was partly what his client paid him for : he seemed to be getting his money’s worth.

After a brief rest, during which I took a few pictures, I spent another twenty minutes piling rocks round my tent. It was well protected on the north side, as Smiler’s tent was less than a metre away, but if the wind went round to the south I would be in trouble, as the view to the south was about as wide open as views ever are. I tried to build the wall up to half a metre on that side, but ran out of rocks and energy. I crawled into the tent, hoping for the best. There was no water at Canada Camp, but I had carried 3.5 litres up with me, so there was no need to melt any snow yet. My evening meal took a while as my stove didn’t seem to be performing very well – it blew itself out several times. I assumed the problem was the wind and the altitude, but cleaned it all the same.

I could hear the wind increasing further, and was dismayed to find it was coming from the south. Not only was there no protection on that side, but the tent was side-on to this southerly wind – the worst possible orientation. I had pitched the foot end towards the west, which is the prevailing direction. The wind was already starting to make the two ends of the tent lean in towards each other, and I didn’t see how it was going to withstand this treatment indefinitely. There was no point in worrying about it – I had already done as much as I could. I had used all the cord that I had with me to set out extra guy lines, and all the energy I had to build up the wall on the south side.

I tried my radio, and discovered that the BBC was now coming in as clear as a bell. I was delighted to find that I could also now pick up a lot of Chilean FM stations broadcasting from Viña del Mar and Santiago. The quality of FM radio in Santiago is excellent by South American standards. There are three stations that play European classical music, another two devoted to classic rock, and another playing a mixture of Caribbean/Tropical music and Latin rock, all with very few interruptions. Listening through my stereo earphones with the volume cranked up, the effect was good enough to take my mind off the wind, which continued to increase in a moderately terrifying fashion.

The pattern of wind was similar to the previous night in Plaza de Mulas – a minute or two of silence followed by an ominous shriek, and the roaring noise of all the tents at Canada being hit simultaneously and bowing under the unstoppable force. I guessed that the phenomenon was caused by the jet stream winds hitting the upper part of the mountain, and being deflected downwards. Every so often a bit of jet-stream would find its way down to Canada Camp, and give everyone there a brief taste of conditions higher up. Whether or not this was the case was largely irrelevant – the wind was still increasing, and I was powerless to do anything to help the situation. I moved over to the opposite side of the tent from where the wind was coming from but could still feel the side of the tent pressing down on me with every gust. I moved back to the windward side, to try and help prop the tent up. As I listened to the thunderous noise of the wind squashing my tent, I was almost certain that eighteen years of use was about to come to a memorable end. It was annoying that this would probably mean I would have to abandon the attempt on Aconcagua, and I began to wish that I had invested in a new, more appropriate tent. Then I tried to decide whether it would have been better for my tent to have been retired gracefully, or whether it was somehow fitting that it should meet its end like this, suddenly, and in a worthy location…