By morning on 17th January the wind had quietened down, and by the time the sun had been shining on the tent for a while it was warm enough to think about loosening the draw cords of my sleeping bag, and seeing what the day had to offer. The first thing I noticed was that ice had formed in the water containers that I had put alongside my sleeping bag. There was not a great deal though, so I decided that it didn’t really justify the discomfort of putting the containers inside my sleeping bag the following night. I had breakfast at a leisurely pace – breakfasts at this altitude consisted of instant porridge mixed with muesli and milk powder, with hot water added, plus a huge mug of coffee. I was continuing to try to drink as much as I possibly could : after breakfast I had to go and collect another bagful of snow.

I lazed around for much of the day, variously listening to the radio, melting snow or just having an extended siesta. Tim, Tork, Dan and Jim did much the same in the morning, and then in the afternoon Tim decided to head up for a day walk to Piedras Blancas, which is an area slightly above Berlin camp, where well acclimatised people occasionally choose to make their top camp. I was content to sit around and look upwards.

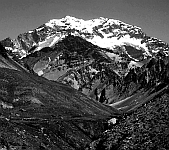

It was very difficult to believe that the summit was as far away as it was, either in distance or time. The air was so clear that distant objects looked precisely the same colour and sharpness as near objects. Also the featureless Gran Acarreo, at the top of which the summit was visible, had the effect of foreshortening the view. Running the eye slowly up the north-east ridge however, one had a truer impression of the distance. I had a look at the aerial photo that I had brought, and it became obvious that however high I felt at Nidos, I really was only half way from base camp to the summit. In fact the photo made it look as though I had barely started ascending the main part of the mountain, so I put it away and resumed listening to the radio.

Later on, after I had had my evening meal, I went down to Tim’s tent and found he was back from his trip to Piedras Blancas. Tork was also there, and after a while Dan and Jim wandered down. Tim said that he was very pleased to have made it to 6000m and having done that he wouldn’t mind so much if he didn’t reach the summit. However, he said he would have two stabs at the summit, one the following day and another the day after, and then go down. He didn’t seem as determined as he had a few days previously – it now sounded as though he was thinking rather reluctantly that having got this far he would have to have a couple of goes at the summit even though what he really wanted was to go straight down. Perhaps he had found his trip up to 6000m far tougher and more unpleasant than he had expected, and he was suddenly thinking that a thousand metres higher than that could well be beyond him.

Tork, too, sounded rather worn out – he didn’t care much for Nidos, and wasn’t sleeping at all well. He was also rather short of time : although he could also afford two attempts on the summit, after that he would have to hurry down in order to catch his flight. Jim and Dan were the exactly the same as usual : Jim sounded confident, Dan sounded cheerful, both claimed they were tired, but neither really looked it.

I was feeling a lot better for having had the day off : I certainly couldn’t have gone anywhere in the morning except possibly down. Tim’s trip up to Piedras Blancas would likewise have been a bit beyond me – I could have done it, but I would probably have felt very much the worse for it. Two of the Canadians showed up, having been up to Berlin Camp to do a carry. Their tent was next to Tim’s. They said that going up to 6000m with heavy rucksacks had taken it out of them.

As the sun started dipping to the horizon two Spaniards returned to a tent nearby, looking extremely tired. They said they had reached the summit after nine continuous hours from Nidos, having set off at 7:00 that morning. They said they had spent a short time on top and had taken three hours to get down. This was encouraging, but Tork said he didn’t feel ready yet to attempt the summit from here, and was reckoning on either waiting another day at Nidos or going up to Berlin Camp the following day. He seemed torn between his dislike of Nidos and the urgency of getting to the top as soon as possible. Tim was keen to try and get the summit over and done with the following day (Sunday) and said he’d be up early to see what the weather was like. He added that if it was at all windy in the night he probably wouldn’t bother getting out of bed until the normal 9:15. I said I’d probably try for the summit with him if the weather was OK, as I felt that the rest day had done me a lot of good, and I obviously needed to do something useful the following day : above all I was keen to avoid the enormous mental and physical effort of moving the tent up to Berlin Camp and pitching it again.

I wandered back to my tent to get my camera, as the view was looking increasingly spectacular in the evening light. I took a few pictures with the sun silhouetted behind one of the smaller “baroque” pinnacles.

I noticed that someone had actually pitched a tent near the top of the main baroque pinnacle, where there was a tiny flat part – it looked an exceptionally exposed spot, even if the peak of the pinnacle did protect their tent well from direct westerly winds. I finished my second roll of film with some shots to the north, where an awesomely spectacular and rather ominous-looking anvil shaped thunder cloud was building, about forty kilometres away.

I went back to my tent, and reluctantly loaded my last roll of film, knowing that I would now have to start seriously cutting down on how many pictures I was taking. I did, however, have to take a couple more of the baroque pinnacles, which were now silhouetted against an orange sunset.

One of the Canadian girls came and joined me and we wandered over to the north side of the ridge to have another look at the thundercloud, which had doubled in length in the space of ten minutes. The anvil head, especially, had grown alarmingly, indicating that the top of the cloud had entered the jetstream, and that the jetstream windspeed was high.

I wondered how much higher the anvil was than the top of Aconcagua – there didn’t seem much in it. I sat up on the crest of the ridge with the Canadian : we watched the cloud change from orange to pink, and chatted about this and that. She told me that two of the group of thirteen Canadians had already given up and were down in Plaza de Mulas. She said that she and the rest of the group were moving up to Berlin Camp the following day. She also told me about her recent backpacking trip to the Colca Canyon in Peru, which I’d never heard of, but she recommended very highly – I made a mental note of this. Eventually we got too cold and went back to our respective tents.

I lay awake for a while listening to my radio, and briefly going over what I would need to throw into my rucksack in the morning if the weather was good enough for a summit attempt. However, I hadn’t been lying there long before I sensed that the wind was getting up – intermittent gusts started to buffet the tent. It sounded like the same sort of pattern as a few days previously, with silence for a few minutes, followed by the whistle of an incoming attack from above. Also, I noticed from my watch that the pressure had been dropping sharply over the last six or eight hours. By midnight there was almost as much noise as at Canada, but without the wind hitting the tent directly. The noise was probably caused by the turbulence as the strengthening westerly wind hit the crest of the little ridge below which I was camped. It appeared that bad weather was returning : clearly Aconcagua was not going to be so straightforward after all.