The combination of a late evening meal and an unpleasant night meant that I didn’t feel like getting up to have breakfast, or even heat up water for coffee. The easiest thing was just to lie there and be warm.

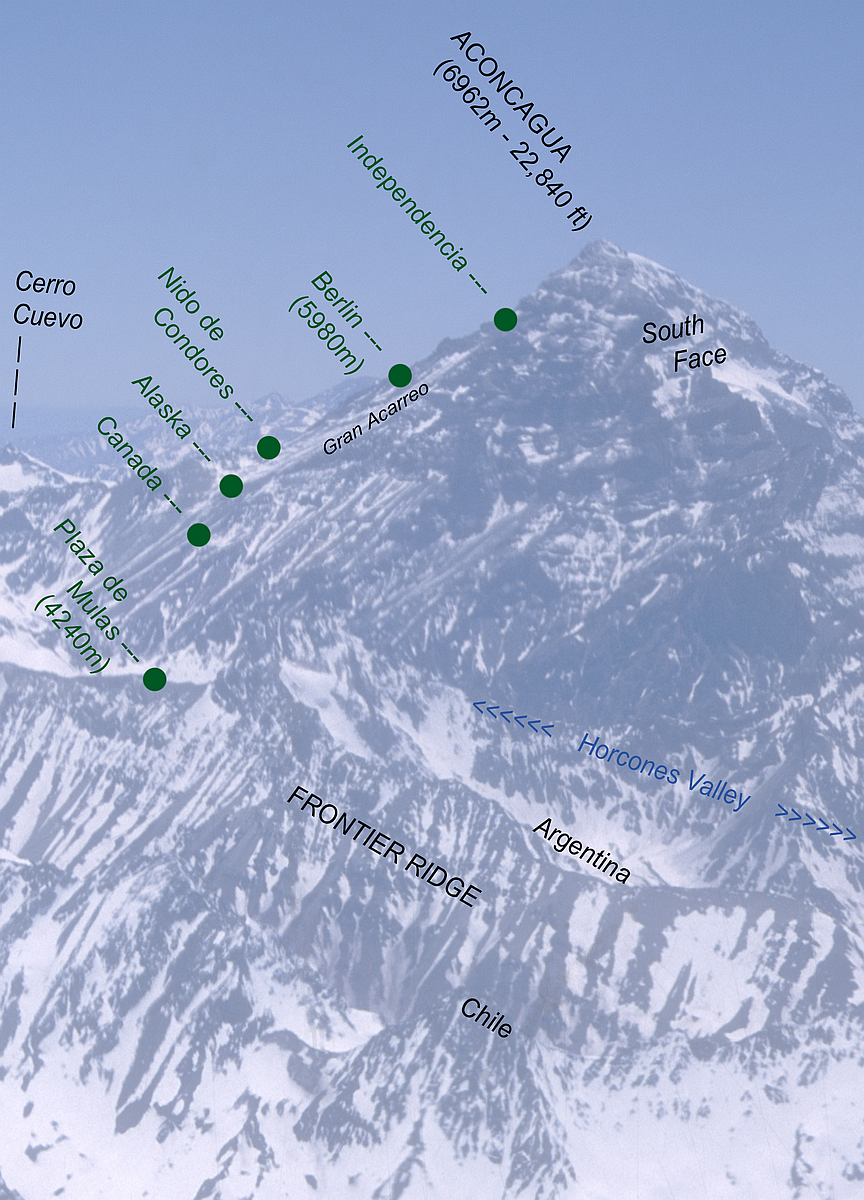

Peering out of the door, we saw that the empty tent was as we had left it, and we worried what if anything we should do about it. It was not as if there was a note from the owner saying where he had gone. Eventually, we heard some noises outside, and a face appeared at the door. As luck would have it, the new arrival was a guardaparque, who had come up alone from Plaza de Mulas. He was new to the park, and had actually come up in the hope of reaching the summit once the weather improved. We told him about the empty tent, and he said he would radio basecamp and make enquiries, to see if the owner was somewhere further down.

The arrival of the guardaparque made us stir our stumps, and we reluctantly got on with a few essential camp chores. Under the current conditions at Berlin Camp, doing anything, anything at all – other than lying immobile in one’s sleeping bag – was an effort involving various degrees of suffering. Consequently, the vast majority of the day was spent lying immobile in our sleeping bags, variously chatting or snoozing, or in my case listening to some Chilean FM station on my earphones.

After we had eaten lunch (cooked by me this time) we had another chat with the guardaparque. He had installed himself in the other hut with the Spaniards. He said that a Brazilian had gone missing a few days previously on the Polish Glacier route, on the other side of Aconcagua, though this would have nothing to do with the empty tent here. He also said that the forecast was for the wind to die down the following day, Wednesday. He didn’t know whether that meant that Wednesday was a potential summit day, or Thursday. Either way it was good news. The wind did seem to be reducing very slightly, and some blue sky was often visible, but there was still a lot of cloud on the upper part of the mountain. The air felt desperately chilly, no doubt because of the increased humidity brought by the weather system.

Later in the afternoon six Brazilians arrived. After a brief interval, their spokesman poked his head in and asked us if there was room for two of them in the refugio, as they only had tent space for four out of the six. It was obvious that there wasn’t room – the fact that both Dan’s and my rucksacks were outside the hut was the proof of that. However, he kept on trying to persuade us, eventually asking if there was room for just one. Jim was adamant that the answer should be no, but of course he didn’t speak Spanish or Portuguese so it was I who was having to speak to the Brazilians.

There may have just about been space for one small person lying crossways by the door, if all three of us had slept all night with our legs curled up. Apart from the discomfort, we wouldn’t have been able to open the door in the night. In case of an emergency this was no doubt what we would have done. Furthermore if three frost-bitten or dangerously exhausted climbers had staggered down into Berlin Camp from above, needing the hut, then we would obviously have moved out and put up our tents. However, Jim’s argument was that this wasn’t an emergency. This was just stupidity on the part of these clowns who had come up without a tent, selfishly assuming that they could use this fact to procure hut space. I found it harder to deny one person the possible space by the door, but foresaw the danger that if we let one in, then the refugio would rapidly become the day-room for all six. I had no wish to spend the next few days even more cramped than we already were, kicking a Brazilian all night long. At the same time, I couldn’t really tell someone to sleep out in the cold. I wasn’t enjoying being Jim’s front man in this, so I climbed out of the refugio to seek the mediation services of our friend the guardaparque. However, by the time I had found him the problem was solved – the two Spaniards had a tent that they would lend to the Brazilians for a small fee.

There was still a persistent ceiling of high speed grey cloud skimming over the upper part of the mountain, but as the afternoon wore on the rest of the sky brightened slightly. It was no longer quite so unpleasant to sit around outside the hut, though after fifteen minutes a return to the hut and one’s sleeping bag was more or less essential. The wind chill factor was still fearsome.

I was also finding it difficult to drink as much water as I knew I should be drinking. Loss of appetite was also affecting me a little, and I was sure I was losing weight. I tried to nibble as much high energy food as I could during the day. Even though I wasn’t doing anything useful I had no doubt that at this altitude I was burning a lot of energy just by keeping all the systems running.

The temperature dropped even faster that night. I thought about putting my recently filled-up two litre water bag in my sleeping bag as well as the 1.5 litre bottle, but when I picked up the bag I found it had already frozen solid. Upon reflection, I decided that I was not prepared to share my bed with a solid bIock of ice, and I left it by the stove ready to try to thaw out in the morning. Jim nobly agreed to set his alarm, and wake us up at seven o’clock if the weather miraculously improved overnight.

I wore my down jacket inside my sleeping bag that night. I was generally warm enough, but an unforeseen problem was that my hands got cold. This was because they generally ended up in the unheated area between the down jacket and the sleeping bag. The suffocating feeling was worse that night, because several times my jacket hood and sleeping bag hood conspired to cut me off entirely from what little air there was at 6000m. Doing up all the various draw-cords of both hoods had produced two small air holes in front of my nose. Though initially the two holes and my nose all lined up, after a while they inevitably didn’t line up any more. I would therefore wake up after a little while gasping for air, and proceed to scrabble around desperately to try to work out which air hole had gone which way. Eventually I would get it figured out, and after a few contortions would manage to get both holes lined up with my nose again. Breathing could then resume.

Jim didn’t wake Dan or me in the morning, as the wind was still gusting viciously past the doorway. Wednesday morning was spent in much the same lazy way as Tuesday morning. The view out of the doorway was very similar. Cloud still sped over the upper part of the mountain. The temperature seemed even lower, and the wind the same as ever. The most important aspect of the weather however was not what we could see outside, but what I noticed when I pressed a button on my watch. The pressure was rising steadily – a very good sign. We began to talk optimistically about the possibility of a summit attempt the following day.

The pressure might have been rising, but I soon had proof that the temperature was lower than the previous day. When I tried to fish my contact lenses out of their case, I found that each lens was encased in a solid disc of frozen saline solution. I had a vague idea that the zero Fahrenheit point was originally defined as the temperature at which saline solution freezes, which was why I hadn’t bothered to put the lens case inside my sleeping bag. However, zero Fahrenheit is only minus 18 C, and it was easy to believe that the temperature had dipped below that overnight.

I duly thawed out my lenses, and eventually crawled outside to get a better impression of the conditions. One of the Brazilians said that the two Spaniards had headed off for the summit, but had started very late. The wind chill factor was still high, and I hoped that they had good gear with them. According to what I dubbed the Idiots Guide to High Altitude Mountaineering – i.e. the booklet that had been issued with the Aconcagua permit – in conditions of high wind above 6000m the wind chill factor is such that exposed flesh freezes solid in twenty seconds.

During the afternoon a number of people arrived at Berlin camp from below. Most of them couldn’t resist the temptation to stick their heads in through the doorway of the refugio. Each person would stare blindly in our direction while their eyes became accustomed to the darkness. They would suddenly see us staring back at them, realise how intrusive they were being, mutter something inaudible and withdraw their head

Gradually the flat area near the hut filled up with tents, until there was probably a total of twenty five people at Berlin Camp. The tent we had lowered two days previously was still there, but the guardaparque had confirmed that its owner was down in Plaza de Mulas.

By late afternoon the wind had moderated substantially, and even in the exposed spots it was probably no more than forty or fifty kilometres per hour. The cloud lifted from the summit for the first time for three days, and it looked as if the long wait was nearly over. However, having been confined to the hut for so long, I was chafing at the bit. Unable to wait until the following morning to discover what the next part of the north-west ridge was like, I suddenly decided to go for a walk up to Piedras Blancas.

I went up very slowly, but felt that I could maintain reasonable progress without excessive exertion. The improving conditions made the mountain seem a lot more tame than it had been for the last few days, and it almost felt like just a pleasant evening stroll, albeit a somewhat oxygen-free one. I had just got past Piedras Blancas, when I saw two people descending. It was the Spaniards – they looked extremely tired and rather downcast. I just said hello as they passed, as they looked in no mood to stop for a chat. Presently I headed back down towards Berlin Camp. Looking down from above reminded me that however busy Berlin Camp was becoming, it really was just an insignificant speck perched on a tiny ledge in a huge expanse of inhospitable mountainside.

When I got down, I asked the Spaniards how they had got on. They said they had made it part way up the Canaleta before giving up. They blamed their failure on the fact that they had spent too long waiting at Berlin Camp : they felt that their bodies had started to deteriorate as a result of being in the death zone. This was really not what I wanted to hear : by the following morning I was going to have been at Berlin Camp just as long as they had been when they had headed uphill that morning. Still, it was too late now – I would just have to hope I was inherently fitter than they were.

We tried to eat as much as we could that night. My evening stroll had made me a little hungrier than usual, so it was easier to get the necessary food down my throat. With the clear sky and the gentler wind, the temperature was plummeting – I made sure that my contact lens case was safely in my pocket that night. If the next day was a potential summit day then getting up would be agonising enough without having to thaw out my contact lenses into the bargain.

That night I was only barely warm enough, even though I had put on every stitch of clothing that I had with me, other than my waterproofs. I even had my woollen balaclava on under the two hoods. This provided yet another air hole to get misaligned, albeit a rather larger one than those left by the draw-cords.

I knew I was supposed to have put both my inner and outer boots in my sleeping bag, but there just didn’t seem to be room. This turned out to be a major error, and the following morning I regretted not having put at least the inner boots inside. As expected, much of the night was once more spent frantically realigning air holes, but there was no alternative. I had to have both hoods tightly done up otherwise the priceless warm air inside my sleeping bag would have just disappeared out of the gaps and floated away, as though it were hydrogen.

When I eventually saw that it was getting light outside, and sensed that there was very little wind, I knew that the next half hour was going to be thoroughly unpleasant. Fortunately I started off warm, so the more delicate jobs such as putting my contact lenses in were done before I had cooled down too much. However it was soon just a race against heat loss : to try to get ready for departure before I got so cold that I was forced back in my sleeping bag to start all over again. I had already decided to dispense with any sort of breakfast, preferring just to nibble chocolate once I was on my way. Jim and Dan were also getting ready, but without quite as much urgency as me. Once I was out of the hut the cold was quite unbelievable. I realised that I would have to get going within a few minutes or I would have no alternative but to go back inside and get in my sleeping bag again. On went my down filled overmitts over my Thinsulate gloves, and I tried to make sure I had no flesh exposed other than the end of my nose.

It seemed that everyone else at Berlin Camp was in the process of doing precisely the same as me – it was as though we had all been choreographed the night before. Everyone was simultaneously climbing out of their tents, sensing the hideously low air temperature, then frantically putting on anything that wasn’t already on, and desperately doing up anything that wasn’t already done up.

To the west I suddenly noticed the spectacular sight of Aconcagua’s shadow stretching out towards the Pacific Ocean. It was very odd to see a shadow that was obviously cast by the sun, because at that moment the sun was still indisputably below the horizon. All the snow capped peaks to the north and west were as yet lit only by the half light of pre-dawn. Aconcagua’s daily prize for being the capstone of the Andes was that it enjoyed the sunshine on its summit while every other peak was still down in the gloom.

I shot off a photo of Aconcagua’s shadow, and was rather alarmed by the noise the camera made as it wound on – the low battery warning indicator also showed. Clearly the camera batteries were suffering from the cold as much as I was. I had a couple of spare batteries keeping warm in an inside pocket just in case, but the idea of changing batteries in those temperatures didn’t appeal in the slightest. After a minute, the summits of the peaks to the north suddenly glowed pink, as the sun rose above their horizon. As they turned orange I couldn’t resist another picture, even though I now had only twenty five exposures left.

My feet were getting seriously cold. Well insulated though my plastic boots were, they had probably been at a temperature of around minus 25 C when I put them on. My feet were therefore having to try to warm the inner boots through a total of sixty degrees Celsius; this was clearly asking rather a lot. I regretted not having put my boots inside my sleeping bag during the night. I had thought that the main reason for this recommendation was so that if the boots were wet they wouldn’t freeze. As mine hadn’t been wet I thought there was little point in suffering the discomfort of squeezing them inside my sleeping bag. The bag was already crowded enough with my 1.5 litre water bottle not to mention all the extra clothes I was wearing.

The only solution was to get going, and quickly. I called out to Jim and Dan who were still inside the hut. Jim suggested that I go on ahead and that they would catch me up : they estimated they wouldn’t be ready for twenty minutes more. That was it : I was out of there.

Most of the other people were also leaving Berlin Camp, and starting uphill in dreamlike slow motion. There were a number of people coming up from below as well, already appearing tired. Looking at them, I was glad I was starting from Berlin Camp, but I wondered whether or not spending three days at 6000m had had a detrimental effect on my fitness.

It was time to find out.