All my various warm layers had been removed, and I was down to just a T-shirt, which felt very strange. I was soon overheating though, and half an hour out of base camp I remembered I was still wearing my expedition-weight thermal longjohns. After a brief pause to remove the offending garment I carried on rather more comfortably down the steep zigzags into Los Horcones valley proper. There were very few people around – I had expected more to be coming up to base camp at that time of day. I saw nobody else going downwards.

After another couple of hours of steady progress down the valley I reached Camp Ibañez. There was just one tent there, slightly higher up than where I had camped before. A moderate breeze had sprung up, and after some thought I decided the upper pitch was better protected. Putting up the tent seemed trivially easy compared with the last time I had done it, nearly 2000m higher at Nidos. There were three Spaniards in the nearby tent – a friendly guy who seemed to laugh all the time, and two shy women who smiled a lot but hardly said a word. I chatted with them for a little while, and then they suddenly decided that it was time for bed, even though it was still light. They explained they were moving up to Plaza de Mulas the next day, and wanted to be away soon after 6am. I couldn’t quite understand why they wanted to leave so early for what was a five hour trek. They said that they hoped they wouldn’t wake me up when they left; a hope I shared.

With the reduction in altitude, my stove had miraculously recovered from its bout of altitude sickness. Preparing an evening meal was laughably easy compared with experiences at Nidos and Berlin Camp : I simply lit the stove and turned it on full. No need to keep a candle burning to re-light the stove every time it blew itself out. The only minor complication was having to wait for the silt to settle out of the stream water. So while waiting for the first bottle of silty water to settle, I melted some snow that I’d “harvested” from some nearby penitentes, to brew my final cup of tea of the trip.

Just as night was falling, two Argentines arrived, having apparently had a minor epic trying to cross the melt water stream. I remembered having seen them on the opposite bank of the stream, looking for a way to cross, when I first arrived. They had had to continue upstream past Ibañez for a couple of kilometres before being able to ford what was now a torrent of melt water. With about half a dozen possible pitches to choose from at Ibañez, they opted to squeeze their tent into the little space between mine and the Spaniards’ – evidently they were social types.

I slept better that night than I had done for well over a week, and was only dimly aware of the Spaniards departing. Eventually the sun warmed the tent up, and I was suddenly itching to get going again.

While I was packing up I got chatting with my two Argentine neighbours, who were heading for Plaza de Mulas that day. They established that I was heading for Puente del Inca, and then carried on commenting on this and that in a typically amiable, extrovert, and slightly brash Argentine manner. After a few minutes they asked how long I had been in the area. When I said two weeks, they suddenly glanced at each other nervously. After an uneasy pause, one of them plucked up the courage to ask the dreaded question : “How high did you get?”. The answer had them cringing with embarrassment, and their demeanour instantly changed to subservient reverence. “Wow, we didn’t realise. Wow. Congratulations!”. They stormed over and pumped my hand. I couldn’t keep a straight face. I asked if they were heading for the summit too. “Well… you know… we were going to try…”, they admitted sheepishly.

I was away from Ibañez by 10:30, and was soon trying to decide whether to stay on the left of the stream, or to try to cross over while the melt water was still low. I opted for the former, but half way down the flat part of the valley I was in any case forced to cross over : the stream ran right alongside the steep loose rock slope on the left hand side of the valley. However, there were trivial amounts of water coming down compared with the torrents of the previous night, so crossing over was no problem. I stopped for my mid-morning snack, and discovered that I could pick up the BBC. I mounted the radio on top of my rucksack, plugged in my earphones, and was thus entertained for the rest of the day.

I began to see my first plants for two weeks. They were a marvellous sight – in fact, the first one I saw, I bent down to gaze at in wonderment. The colours seemed to be incredibly bright and vivid, though after two weeks of seeing nothing but blue, white and grey I was very easy to impress. I had to cross the stream twice more, and at the second crossing point the water had risen considerably, covering the stepping-stones. However, the streambed was sandy, so off came my trainers and socks, and I happily paddled around in the cool muddy water for far longer than was necessary to cross the stream. It was ecstasy.

I began to look forward to drinking water from the crystal clear stream that was just above Confluencia. I remembered the way the Japanese had been gratefully splashing around in it when I had been on the way up. Eventually I reached it, and decided that no water had ever tasted so good. It was as yet too early for lunch, so I headed on down through Confluencia Camp, over the rickety bridge, and up the other side.

Eventually I called a halt, and began finishing off the remnants of my lunch goodies. I had no crackers left (they had gone missing at Berlin Camp) so I ended up spooning straight into my mouth a mixture of salmon pate, peanut butter, and the last bit of smoked cheese. It was surprisingly edible.

I carried on down the steeper part of Los Horcones, saying hello to a number of what seemed to me to be ludicrously clean, pale, shaven, and well-groomed mountaineers slowly coming up the path. Nobody asked me anything, but my high speed downhill was probably a deterrent to small talk.

The culture shock of returning to civilisation began with the view of the little suspension bridge over the river. It continued a couple of kilometres further on when I reached the lagoon and the first of the day-trippers. They looked at me curiously, but I was sure that I couldn’t have appeared any more extraordinary to them than they did to me. Even weirder sights were in store for me another kilometre down the path : a distant view of vehicles by the park entrance.

I couldn’t stop myself looking behind me every minute or two. The view of Aconcagua had returned to being that of the huge distant unassailable white monster, at which I had gazed rather doubtfully from this very spot fifteen days before. Looking up at the summit, it was very difficult to relate what I now saw, with my memories of forty-eight hours previously.

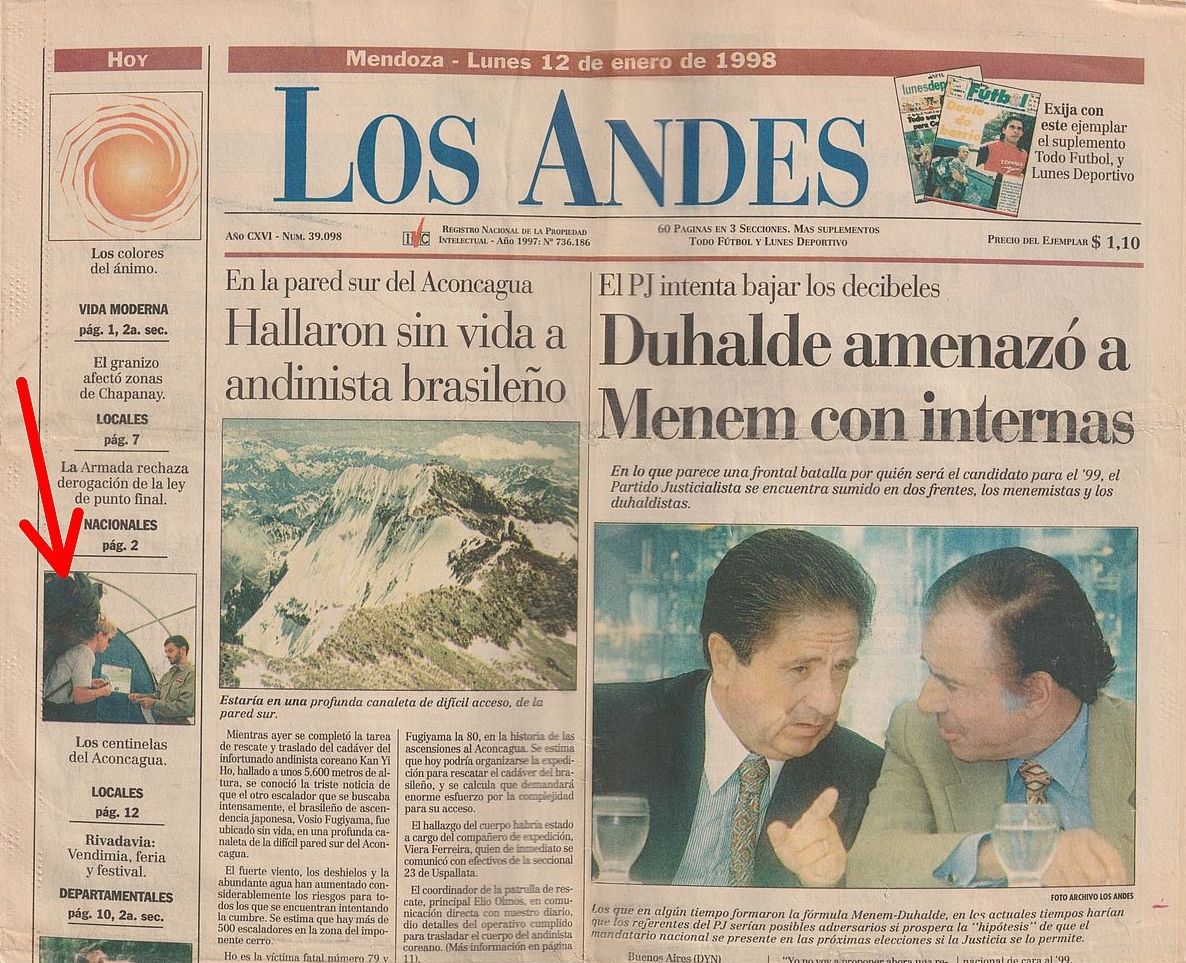

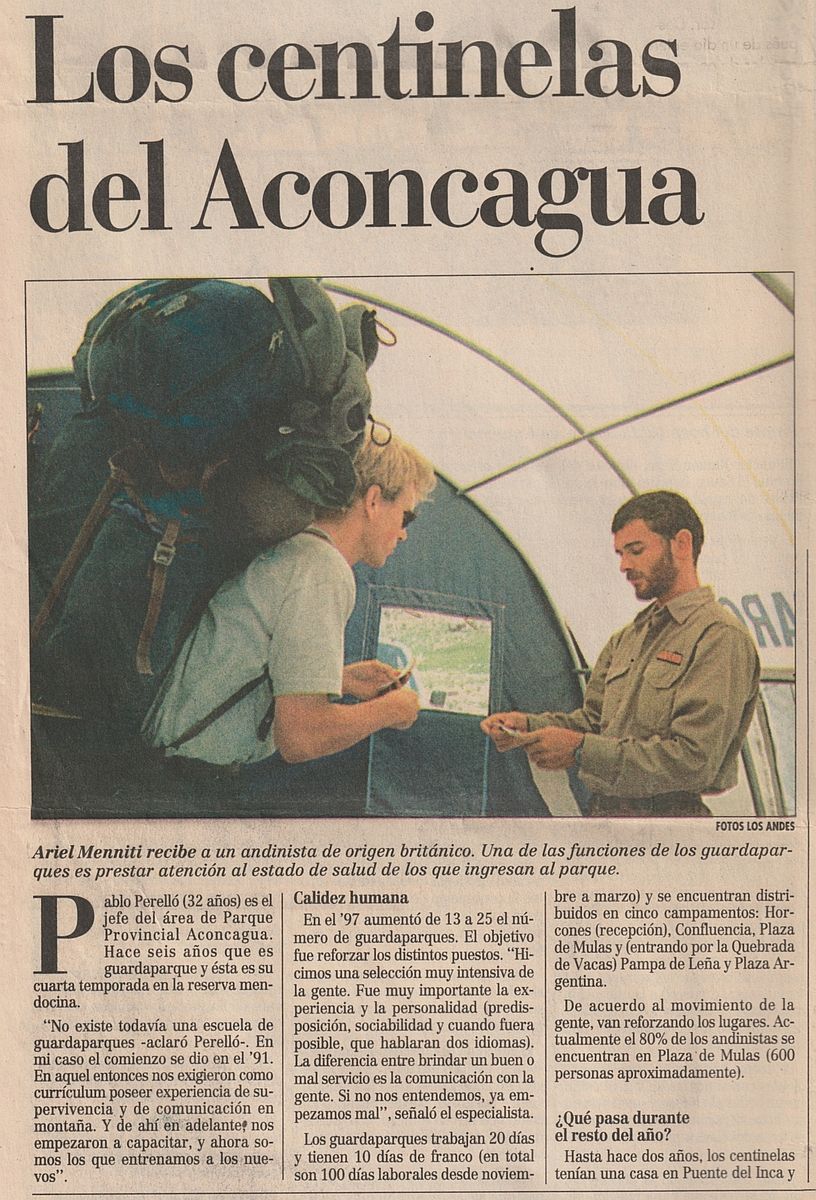

Finally the wilderness experience was over. I marched up to the guardaparques’ tent to hand in my rubbish and report my exit from the Aconcagua Provincial Park. The rumour was that the failure to arrive with one’s rubbish bag would incur a fine of $100 (apparently the system used to be that anyone who did arrive with their rubbish bag was given a can of beer). Ariel, the guardaparque, came bounding out grinning broadly, as I announced that my mission had been accomplished. “You and I looked great in the newspaper!”, he announced. I looked rather blank.

Ariel explained that the journalist who had taken our photo had been from the “Los Andes” newspaper – the principal daily for the whole of Mendoza Province. She had written an article about the work of the guardaparques in the Aconcagua Provincial Park. The front page had had a small photo of Ariel and me, with some brief details, and the main article had been on the back page, with a much larger photo of the two of us.

The article mentioned my name, that I was British and worked in the oilfields of Argentina. It contained my remark to the journalist regarding my disappointment at the amount of rubbish by the sides of the main road over the Andes, in what should be kept as a pristine wilderness.

Unfortunately Ariel had sent the only copy he had with him up to Plaza de Mulas, so that all his friends could see it. Apparently the guardaparques were all very proud of the article, and Ariel and I were the heroes. Ariel was now delighted to discover that his co-star had made it to the summit.

I had made it to the park entrance rather sooner than I had expected – it wasn’t even 4pm yet, so it had taken less than a full day from Plaza de Mulas. It was remarkable to think that it had taken fourteen days to get from here to the summit, whereas to return from the summit to here had been the result of no more than eleven hours’ worth of walking.

The plan at this point had been to go down to Puente del Inca and stay the night, and to arrange to be picked up the following morning by one of the Mendoza-Santiago buses. However, as it was so early, I asked Ariel if he thought there was any chance of getting a ride straight to Santiago that afternoon. He seemed to think it was possible, and that the best thing was just to wander down to the immigration building and see if the last scheduled bus had gone through yet. I considered the tantalising prospect that in four short hours I could be having a shower in the unimaginable comfort of my own apartment. The prospect was irresistible.

Off I trotted, on just two legs now : I had finally strapped my ski sticks to my rucksack. I had decided that I was going to look sufficiently weird walking into the immigration building as it was, even without my ski sticks clattering on the concrete floor…

After walking downhill for a kilometre, I reached the immigration building, and the culture shock was completed. I suddenly had to cope with the bewildering sight of cars, buses, offices and computers. However, rather than feeling that I was returning to normality, what I felt was that this all looked very much out of place up here in the Andes. I couldn’t avoid the thought that this incongruous outpost of civilisation was, when compared with the surrounding mountains, a very small and temporary aberration.

As expected, I got a few curious looks from people. The majority of the tourists in the long queue of vehicles seemed to be Argentines heading for the Chilean seaside resorts, and many of them were already dressed for the beach. Observing this, it was easy to feel that it was I who was dressed and equipped appropriately for the surroundings, and they who were the abnormal ones. The problem was that there were a lot more of them than there was of me.

I established that the last bus to Santiago had not yet passed through. After half an hour of impatiently wandering up and down the queue of cars, a bus from the Chilean company Tur-Bus came chugging up the switchbacks. As I had expected, it jumped the queue, and sneaked round to the vehicle exit at the far end of the building, with me in hot pursuit. The driver said that there was space for me, but that as I was not on the passenger list I would have to obtain a “pax” form from immigration. This was some bureaucratic necessity that involved the further culture shock of going upstairs to someone’s office to fetch a slip of paper to present to the immigration people.

Giving me my exit stamp, the young immigration officer treated me coolly until he had done the official part. His manner then instantly warmed, and he asked rather surreptitiously : “did you make it to the summit?”. Clearly experience had taught him that dirty smelly foreigners with large rucksacks and “pax” forms are invariably on their way back from Aconcagua.

I had been concerned that on the bus some poor soul might have to sit next to me, but luckily there were sufficient spare seats. Finally the bus was speeding westwards. None of the other passengers glanced up at the brief view of Aconcagua. I couldn’t keep my eyes off it this time, but it looked no different from normal : it was difficult to accept that I had now climbed it. It was also difficult to accept that the only way I would be able to climb any higher would be to go to the Himalayas or Karakoram.

In fact, on the way back to Santiago, it occurred to me that the existence of the Himalaya / Karakoram range is very fortunate indeed for the sport of mountaineering. The failure rate on Aconcagua may be high, but the sport would lose most of its mystique if it were the case that an upstart such as me could simply take two weeks off, pack a rucksack, hop on the bus, and conquer what would otherwise be the world’s highest mountain…

Santiago felt insufferably hot even though it was gone 8pm when I arrived. The taxi driver who took me back to my apartment probably wished that he had a glass screen or a stretch limo : anything to isolate him more effectively from this unusually smelly passenger.

As the guards at the entrance to the condominium waved the taxi through, little did I know that the biggest fright of the entire trip was yet to come. Having paid the taxi driver, I dragged my rucksack into the foyer of the apartment building, and pressed the elevator button, smiling happily to myself at the thought of the imminent shower, clean clothes, and unlimited food. In theory, the only people allowed past the gate are residents and specifically authorised guests. However as the door to the elevator opened, it was clear that the guards were not doing a very good job at keeping out disreputable looking vagrants. There, in front of me, was a terrifying, emaciated figure, with an insane expectant grin, a filthy lopsided T-shirt, streaky unkempt hair, unshaven chin, peeling face, hands black with ingrained dirt, cracked fingers bound with tattered plasters… I dragged my rucksack into the empty elevator and pressed button number ten, wishing for once that the builder had fitted the rear wall of the elevator with something other than a large mirror.

M.J.G. January 2023

And finally, a quick word of thanks:

Thanks everybody for reading my book. I hope you enjoyed reading the blog as much as I enjoyed writing it!

Gracias a todos por leer mi libro. Espero que hayan disfrutado leyendo el blog tanto como yo disfruté escribiéndolo!

Excellent Malcolm, I really enjoyed the read and all your spectacular photos.

I laughed at the ending, it reminded me of my first night in a hotel in Pokhara 40 years ago. I looked at my self in a mirror for the first time in a month and it was shocking. A trek in the Himalayas had left me a dirty bedraggled 10 stone waif and I don’t know if my mother would have recognized me.

Malcolm, so glad you achieved your goal. Great photos and commentary; I like the way you have written about your experiences. How did you produce the videos taken during your trek?

What a shame your it had to end – no more episodes to look years to . I don’t suppose you have any further adventures to share?

Terrific! Definitely worth revisiting.

So where did the snow come from in the video? Fridge freezers are frost-free these days? Wind effects were splendid. That wind would have driven me mad also.

You think it’s not real snow from Aconcagua..?

(The Thermomix works wonders on ice cubes when you suddenly need snow… 😉 )

I am exhausted just at the thought of this trip! Thank you for sharing again, I remember the days awaiting the next installment!

Another fabulous journey! I am so glad you shared this story with all of us! Cheers, my friend!